How Jerry Springer Saved My Hospice Shift

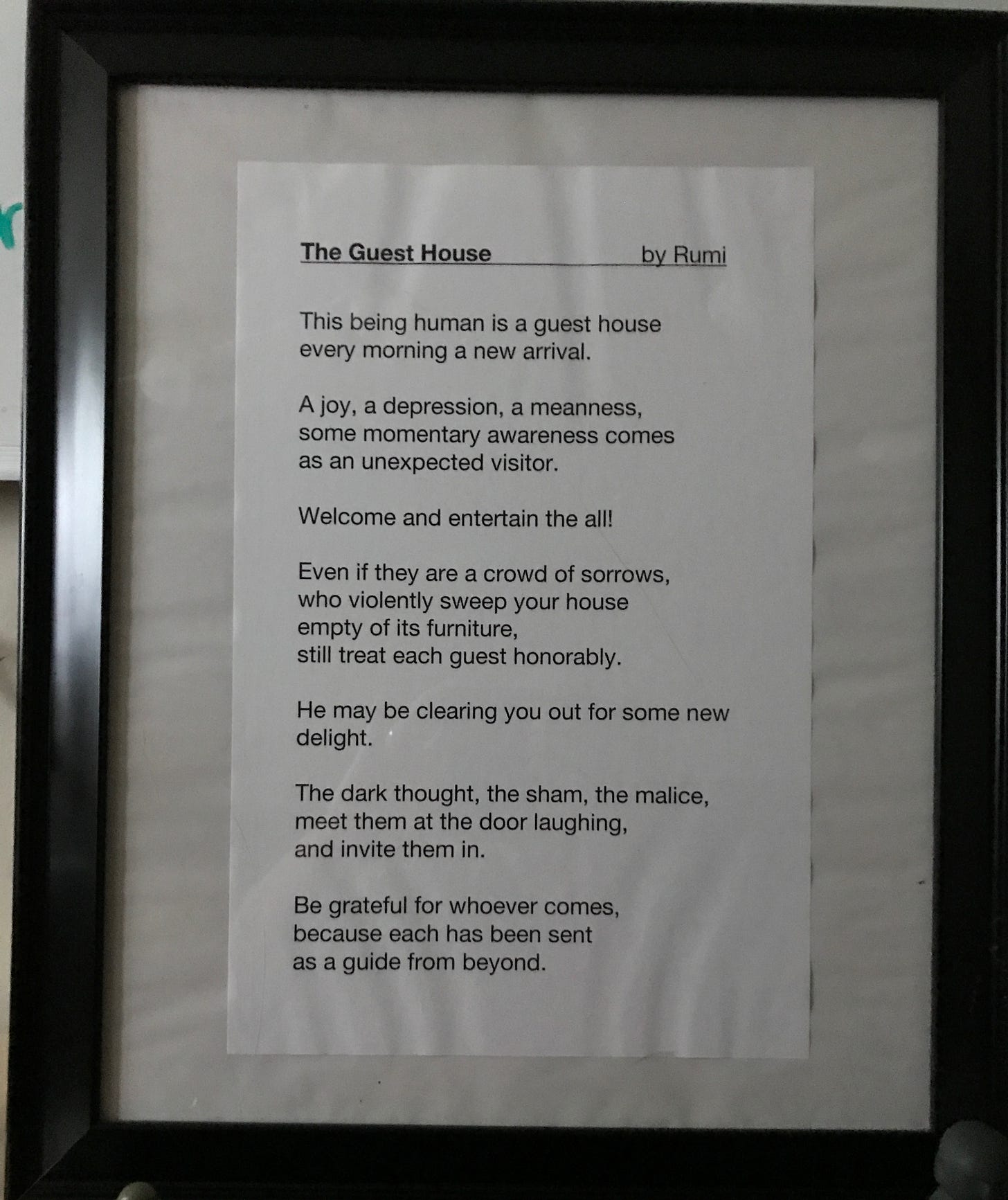

A lesson in empathy at the Guest House.

When I heard that Jerry Springer had died last week, my thoughts immediately went to my second-ever shift at the Zen Hospice Project, in 2014. I’d been having a hard time connecting with a just-admitted resident (at ZHP, blessedly, they weren’t referred to as “patients”), a woman I’ll call Donna.

When I first saw Donna, I was standing in the doorway to her room, the one room in the Guest House that was subsidized so that indigent people could be cared for there. A tiny Black woman, she was curled up in her bed in a strange, twisted, painful-looking shape, wearing the tattered gown she’d arrived in, her head pressed against the wall. The nurses came in and out, administering pain meds, trying to get her comfortable. She yelled at them when they tried to change her into some clean clothes from one of the many garbage bags around the room; the contents of those bags, I would learn, were her worldly possessions, with the exception of an enormous electric wheelchair, which was parked downstairs. She was moaning loudly, but I couldn’t make out what, if anything, she was trying to say.

I was new there — their first-ever artist-in-residence, taking two volunteer shifts a week to gather stories for an eventual benefit performance. (Later, after my residency was over, I went on to volunteer there for several more years.) My shift-mate, Lisa, joined me in the doorway; she was dealing with other residents, but wanted to see how I was getting along.

“I don’t know what to do,” I told her, as we stared in at the moaning woman.

“Why don’t you go in and ask her if she wants anything?” Lisa suggested.

Simple, right? But actually, not so simple. The truth is, I was terrified. Terrified of getting close to a person who was dying and in pain. Terrified that I wouldn’t know how to help her, or would do something that would actually add to her suffering.

Nonetheless, bolstered by Lisa’s matter-of-factness, I entered Donna’s room and went up to her bed.

“Hi, I’m Josh,” I said. “Can I get you anything?”

After a pause, Donna — still not looking at me — made a guttural sound.

“I— I didn’t get that,” I said. “Could you please say it again?”

The same guttural sound, but louder this time.

“I still—”

Donna turned her face partly toward me. She looked to be in her 60s or 70s. I later learned that she was in her late 40s.

“Water!” she said.

When I came back from the kitchen with a glass of water and she had taken a few sips, she turned away from me again.

After a few minutes of silence, I said, “Can I get you anything else?”

No answer.

I pulled a chair up next to her bed and just sat there for a while.

There was a TV in the room. I went over and turned it on. At 3 p.m. The Jerry Springer Show began. Instantly, Donna yelled, “Jerry!” She rolled over to see the screen. I shifted a couple of pillows to prop up her head, then turned up the volume on the TV.

On the show, Jerry was explaining that a young woman had been wronged: she’d caught her fiancé sleeping with her sister. He invited the woman onstage. To visually underscore her situation, the wronged woman was wearing a wedding dress.

After the woman had told her sad tale, Jerry revealed that her ex-fiancé was actually backstage: “Let’s bring him on!”

The guy explained to his ex that, well, he’s a man, and her sister came on to him, so what could he do?

“That’s just wrong!” Donna said. For the first time, she was making real eye contact with me. I got the sense that she wanted to see what kind of person I was.

“Yes,” I agreed, “that is just wrong!”

Donna gave me a little, approving nod, as if to say: Okay, so you do have a moral compass.

Later on that Springer episode, Jerry brought out the sister — and wouldn’t you know it, somehow a wedding cake appeared on stage — and also, wouldn’t you know it, somehow the wronged woman ended up smooshing that wedding cake into her sister’s face, and a brouhaha ensued, involving the sisters and the ex-fiancé and some other family members and friends — and throughout all of this the studio crowd periodically chanted, “Jerry! Jerry! Jerry!” Donna and I remained glued to the screen the whole time.

From then on, Donna trusted me. Kind of. Provisionally. On each of my shifts, I’d make sure to join her in watching Jerry Springer. And as the weeks went by, she told me stories from her tragic life. As a child, she’d been poor and religiously devout. She was such a beautiful teenager that people suggested she might become a model. (I never saw the photo she had of herself as a teen, but another volunteer did — and confirmed that Donna had, indeed, been strikingly beautiful.) Donna said her best friend got addicted to heroin, and kept trying to get Donna to try the drug. Once she did, she got hooked, and her life descended into hell.

When Donna arrived at our hospice, she’d been homeless, on and off, for years. She’d been on drugs fairly constantly. And now her body was wracked with cancer. There were few moments of respite in her life now — but some of them were when she got to watch The Jerry Springer Show. And I got to share them with her.

Once, when I had just arrived for my shift, a nurse told me I should hurry upstairs to see Donna, who had been calling out for me. Not by name — I’m not sure she ever addressed me as “Josh.” Rather, she’d been yelling that she wanted “the bald guy.” Now, as it happens, one of the staff members, Jeff, was also bald — but in a cool, young, fit, shave-your-own-head, one-earring-stud kind of way; whereas my baldness was genetic, and decidedly uncool.

As I climbed the stairs, I could hear Donna still asking for “the bald guy.”

Someone asked her, “Do you mean Jeff?”

“No!” she bellowed with exasperation. “Not that kind of bald!!”

Despite my baldness, I found many of Donna’s stories to be hair-raising indeed. One of them involved a cousin of hers, a professional hitman who had, in the end, himself been hit. After his violent death, she told me, all that could be found of him were his two thumbs. She gestured for me to lean in close so she could give me an important piece of advice: “Never — never — steal from an Oakland drug gang!”

I told her I would never steal from an Oakland drug gang — and reader, this is a promise that I have kept.

Though Donna’s medical situation stabilized somewhat over the coming weeks, she remained extremely paranoid — the legacy of her years of poverty, homelessness, and drug addiction. She kept thinking that someone at the hospice was going to steal her prized electric wheelchair, and she kept its key hidden somewhere in her room. Sometimes she got violent with nurses and volunteers. And when she began calling the police in the middle of the night to come and “rescue” her from the hospice, it became impossible for her to stay. She was moved to a much-less-nice facility in the Tenderloin. I am very sad to say that I never got a chance to visit her there before she died.

And of course dying is what people come to hospice to do. But I think it may be truer to say that people come to hospice to live. A beautiful facility like the Guest House of the Zen Hospice Project allowed mortally ill human beings to experience, as much as their condition allowed, peace and joy and beauty and love. Alas, the Guest House is no more. Our society doesn’t yet properly value such services — doesn’t yet see the need to bring dignity and comfort to the end of people’s lives. Donna was able to spend her time at ZHP because of the generosity of an individual donor — a tiny bit of grace after a lifetime of being ignored and abused.

Jerry Springer always ended his show by telling his audience, “Take care of yourself — and each other.” Righteous words. Now let’s back them up with activism, policy-making, and funding.

Josh. I have been fortunate enough to have had some very moving and sometimes even humorous times working and talking with the street people who lived around my Denver VISTA neighborhood back in the late 60s. They helped me perhaps more than I did for them by giving me a compassionate understanding of the many paths that lead too many to the invisible depths of our society. Thanks for sharing one of your experiences.

You're a true mensch, Josh. I wish I had your empathy and people skills.

There are many folks like Donna just outside of the SF Friends (Quaker) Meeting House, which I've been attending for a few months. Some of our Friends help them when and as they can. But a city of such tremendous wealth can and should house every one of its residents, and treat them with the dignity they deserve.