Where is my mother?

I must have been about five or six years old. On certain weekdays someone (possibly Mrs. Mann, the woman who used to take care of me) would drop me off in the late afternoon at the uptown Port Authority terminal on 178th Street, at the foot of the George Washington Bridge, to wait for my mom to return from Teaneck, New Jersey, where she worked as a librarian. Her bus would come in, and then the two of us would take the city bus to our apartment on 162nd Street.

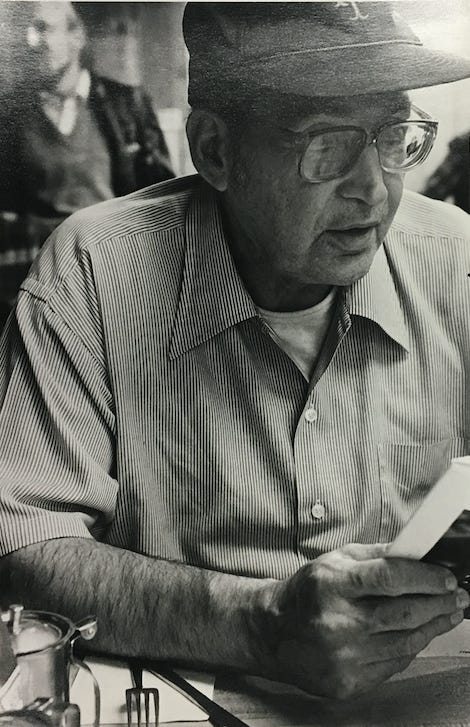

I loved hanging out at the Port Authority! I felt free, footloose — exhilarated even, especially when I spent time at the bookstore. The young woman behind the counter cheerfully indulged my presence, as I explored Fiction, Self-Help, Classics, and more; eventually I had the entire store’s shelf layout memorized, and could guide shoppers to the section they were looking for. On certain days a small, quiet man took the woman’s place. My mother once told me that this was Carl Solomon, to whom Allen Ginsberg had dedicated his famous poem “Howl.” Mom said that Carl, who she knew somehow (I think they may have been in a writers’ workshop together), had been in a mental institution. What could that have been like for him? I’d wonder. His smile was gentle; his focus seemed inward, even as he rang up sales.

Sometimes Mom, after getting off the bus, would find me at the bookstore. But not on this day. Eventually I wandered out to the newsstand. I looked through the comic-book section, to see if there was a Spider-Man that I hadn’t read yet. Out of the corner of my eye, I thought I saw Mom stride past — so I ran out to try to catch her, making it halfway down the stairs before deciding that it couldn’t have been her. There was an upward tug on the back of my shirt collar. It was the newsstand operator; he thought I’d stolen something and was trying to make my getaway. I showed him that all I was carrying was a book I’d gotten from the bookstore — well, Carl Solomon had bought it for me, using his employee’s discount. The newsstand operator let me go. I felt shaken up.

People kept streaming through the Port Authority, but none of them were my mom. I had a nickel in my pocket. When I was a child, it was common for adults to regale me with what, in their childhoods, they could get for a nickel: a ticket to a double feature at the movies, a bagful of candies from the corner store, a subway ride, world peace. Even now, my father, Paul, and I could — and frequently did — take a roundtrip ride on the Staten Island Ferry for just a nickel, when he had me on the weekends. I went into a phone booth, thinking I’d try reaching my dad at his apartment on the Lower East Side. At the top of the payphone were slots for three kinds of coins: quarter, dime, or nickel. I’d always assumed this meant that you could call someone for just a nickel — though probably for only a short time. But when I put in my nickel, I couldn’t get a dial tone. I pressed the coin-release, got my nickel back, and tried again: still no dial tone. I tried this over and over and over. This didn’t make sense! The world didn’t make sense! (Turns out you needed at least a dime to make a call — or an extra nickel.)

Finally, I gave up on phoning. What should I do now? I decided that I should try to walk home on my own. (Why didn’t I try taking a city bus? I don’t know! Maybe I’d take the wrong one and end up in a strange and distant land, like Queens?) Outside the terminal’s exit on Fort Washington Avenue, I didn’t know whether to go right or left. I went right. The street numbers were going up — wrong direction! I turned back the other way. Over towards the Hudson River, to my surprise I saw what looked like a separate little city on a hill: a cluster of tall buildings, with people walking around dressed in religious Jewish garb. (Has that always been here? If so, I never noticed it before.) It occurred to me then that there were so many things in this world that I hadn’t yet experienced, or even imagined. This was thrilling to contemplate.

Also thrilling was my sense of aggrievement. Mom didn’t pick me up! Did she just forget about me? This aggrievement felt like something sweet and pure that I had earned through this harrowing experience, and now was mine to cherish.

It was dark. I saw that the moon, my friend, was following me as usual, which comforted me.

And the street numbers kept going down. At the corner of 162nd Street, I turned right. Someone was just coming out of my building when I got there, so I didn’t have to press the buzzer. The door to our apartment was unlocked. I opened it and walked inside. My mother and father were in the living room, sitting on the couch.

I’d never seen them like this! Together! Usually Dad would go no farther than the doorway, standing tensely in the hall when he picked me up or dropped me off. But there they were, next to each other on the couch. And not yelling at each other!

“We called the police,” Dad said. “They’re out looking for you.”

“You didn’t pick me up at the Port Authority,” I said to my mom.

“I didn’t know that I was meeting you there today,” she said.

“I only had a nickel, and I couldn’t make a call,” I said.

My book from Carl Solomon was in my lap.

For the only time that I can remember, the three of us hugged one another as a family.

This story has so many important elements. The benevolent adult friends/staff in the bookstore, the unease and ultimate triumph of being lost and figuring out the way home, the nickel as talisman! Thank you for conjuring the weird magic of coinage back in the day. And for honoring the smarts of a lost kid. A fine thing to picture the rare family trio, too.

I feel a sadness for so many children today, hovered over, but suppressed by loving parents who are fearful of allowing them to explore the world around them as I did growing up in a small town 60+years ago. Perhaps I would feel differently if I had ever had children of my own. You, Josh, had a much richer and exciting world to explore than I did. Still, I am very grateful for the freedom that I was allowed in an admittedly more safe environment.