It all started with an elective I took during my second year at Princeton: an introductory acting class with Paul Zimet, of the experimental New York theater troupe the Talking Band. A couple of years earlier, I’d entered college from the Bronx High School of Science, secure in the knowledge that I was going to become (as my father, Paul, assured me) the greatest mathematician who had ever lived. Then, alas, I’d actually taken freshman calculus, and boy howdy, was I not brilliant at it! As I describe in my solo show The Mathematics of Change, I was tragically unable to grasp how 0.999… — those ever tinier and tinier .9’s extending out into infinity — could possibly end up equaling 1. After spending the first half of my sophomore year ascertaining that I was similarly un-brilliant at physics, chemistry, or biology, I declared myself a politics major (mostly just planning to take classes with the radical political theorist Sheldon Wolin) and — to fill out my spring-semester schedule with something that might be a fun distraction — signed up for that acting class. At the time I had no idea I’d end up becoming a performer myself, or that Zimet and his Talking Band colleagues, Ellen Maddow and Tina Shepard, would end up guiding me, somehow, toward experiences that would challenge my self-identity — that still do.

I don’t remember that course with a ton of detail. It was in an old wooden house on Princeton’s main drag, Nassau Street. I do recall sunlight streaming in through a nearby window as I stood with a female student and we explored each other’s foreheads with our fingertips. Why were we doing this? I think it was to receive each other’s emotions, or even thoughts, in a tactile way. In any event, I was unbelievably nervous! I wasn’t just a virgin, I was kind of a super-virgin: touching a girl — holding hands, even — made me shake uncontrollably. This forehead thing — well, it just seemed so … intimate. What’s weird is that, at the same time, I’d had no problem, at a previous session in which we’d been asked to portray someone we knew, depicting my dad’s friend Marv Stern talking to me about sexual matters in the most explicit ways. I guess it was a complicated kind of shyness that I possessed: able to be bold when acting as someone else, but nearly frozen by timidity when just being me.

During the semester Zimet curated some performances by visiting theater artists. One of these was a production of Anton Chekhov’s Three Sisters, with a cast that included a remarkable actress named Lois Smith. Zimet arranged for us to sit in on a rehearsal — and I was struck by how Smith spoke so much more quietly than all the other actors. You could make out everything she was saying, but you had to lean in. There was a vulnerability to her — not just in her speech but in her manner as well — that I found absolutely magnetic. And unsettling — as if it were untoward of us, intrusive, to experience her in this way. She wasn’t acting; she was being. I assumed that at the official performance of the play, that evening, she’d amp up the volume and declaim like a “real” actor — only to find, to my amazement, that she retained all that quiet tremulousness, that sense of rawness, of improvisation. Maybe I sensed in Smith a hint of how working in the theater might help me explore the tensions I was sensing in myself: between extra- and introversion, between wishing to proclaim myself to the masses and going to hide in a corner … between acting and being.

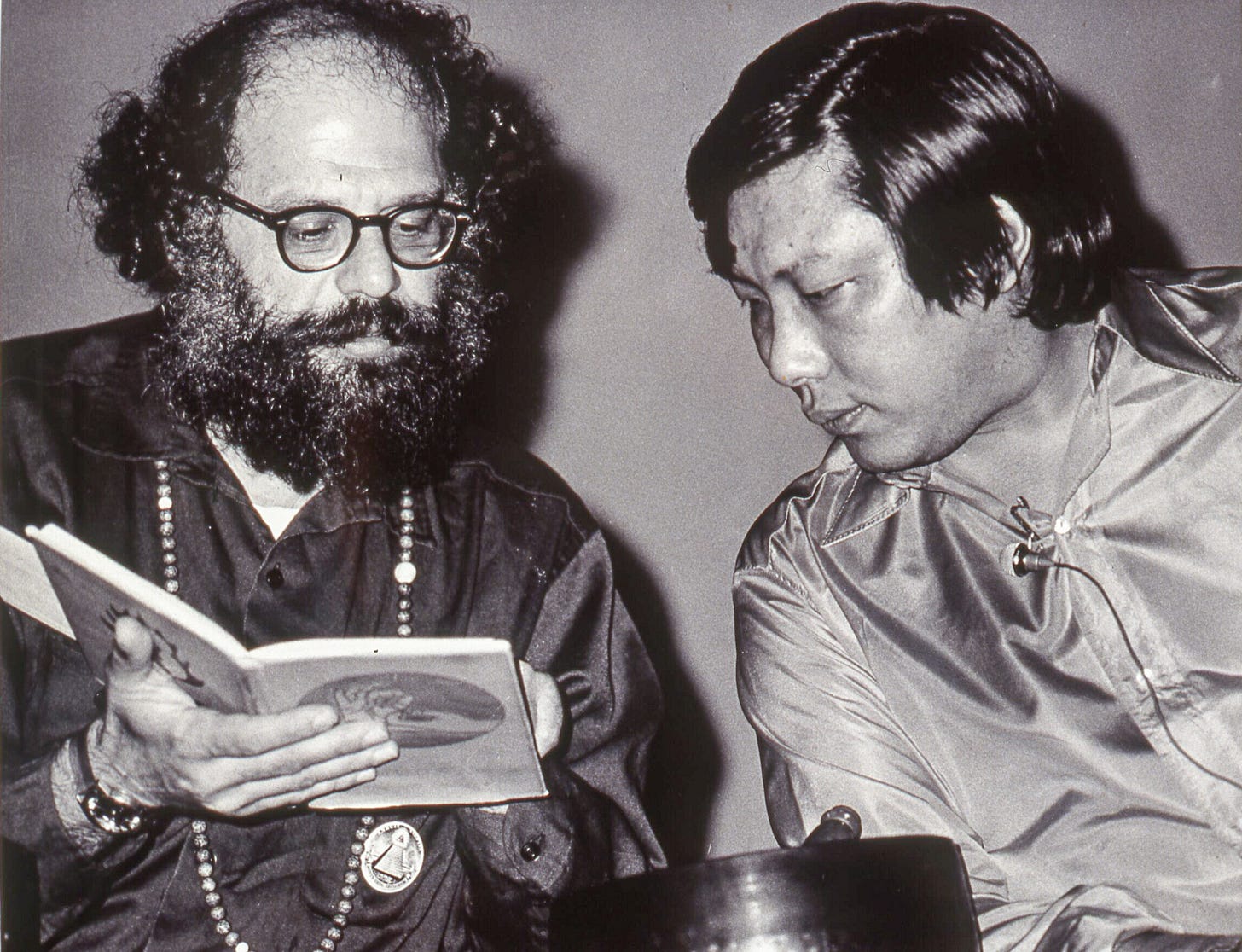

At our next class session, I told Zimet that I was getting inspired to pursue theater a bit further. And that’s when he told me that the upcoming summer he and the rest of the Talking Band would be in residence at a place called Naropa Institute (since its later accreditation, it has become Naropa University). I went to the library to find out about Naropa. (This was, um, quite a few years before Google.) It seemed magical — kind of like something out of a Buddhist fairy tale. Nestled in the Rocky Mountains, in Boulder, Colo., it had been founded by a Tibetan sage named Chögyam Trungpa. Among its departments was the fabulously named Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, co-founded by poets Allen Ginsberg, Anne Waldman, and Diane di Prima and composer John Cage. I cannot emphasize enough how everything about Naropa was the opposite of what I thought I’d been raised to be: a Marxist-Leninist with his feet firmly planted in the landscape of Western thought. So it came as a total surprise when, in a phone call to my mom, Bunny, to tell her I was toying with the idea of spending the summer at Naropa, she excitedly began talking about how great this Chögyam Trungpa guy was!

But Mom had been getting into meditation lately. I don’t know if this was, in part, a reaction to the intense nature of her new job. A cataloguing librarian, she’d been hired by the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research to organize the huge amount of photographs that had been donated. Many of these photos were from the Holocaust, and my mother found that she couldn’t bear to look at many of them — which created quite a challenge, as she needed to generate a detailed catalogue entry for each one. YIVO allowed her to hire a young grad student from Columbia University to, so to speak, be her eyes on these pictures. He’d describe each one to her in great detail, enabling her to type it up for the catalogue. I remember this grad student, Jim Hoberman, as being quiet and kind — and was delighted when (under the byline “J. Hoberman”) he later went on to become a prominent film critic with the Village Voice.

“Oh, you have to go to Naropa!” Mom said on the phone. “Trungpa’s books on meditation are the best! It’s all about how you breathe.”

Well, I didn’t have any interest in meditation. And as for focusing on breathing — that just sounded silly! But Paul Zimet and his Talking Band pals were going to be teaching a class there, and it would undoubtedly be, well, different. As a friend of mine noted after I told him about Naropa: “Josh, I think you may finally get laid!”

Well, that certainly would be nice.

I got in touch with someone at Naropa, a woman I’ll call Nina, and pretty soon I’d signed up to spend the summer there, working part-time and taking Zimet’s class. Combined with my relief at having given up the mathematical ghost and my giddy anticipation of exploring radical political theory the following school year, this upcoming summer adventure made me feel as though finally — finally — I’d found a path forward, away from my parent-dominated childhood and toward a rich, independent future. It was all coming together!

On the last week of that spring semester, I was talking on the phone with Nina. She’d been arranging both my work schedule and my accommodations, and we were finalizing some details — including when my plane would be arriving in Denver, so she could pick me up and drive me to Boulder.

She said, “Oh, and will your mother be joining you on that flight?”

I laughed.

She said, “No, really.”

I went into total shock. “What???”

Nina said, “You know that your mom volunteered to work in Naropa’s library this summer, right?”

That year at Princeton I was living in the New New Quad, a rather isolated place that, I came to learn, was populated largely by social misfits. As a sophomore, I was supposed to still have a roommate — but after I’d pleaded my case to the folks at Campus Housing, emphasizing my intense shyness and general oddball-osity, they’d finally allowed me to have my own room at “the quadrangle.” Only, it was an incredibly narrow room! You could pace up and down, but not move side-to-side. I remember pacing that afternoon — door to window, back and forth — as I pleaded on the phone with my mother, who was at work at YIVO. I felt desperate — invaded — on the verge of losing my mind. This was right after I’d hung up on Nina.

“Mom, you can’t go to Naropa! That’s my thing!”

“Oh, Josh, you won’t even know I’m there!”

“I will know you’re there!!”

“I’ve always wanted to take meditation classes with Trungpa.”

“Take them next summer!” I said.

“I want to go this summer!”

“But you knew how excited I was about going there! And you never mentioned anything to me about wanting to go there yourself.”

“It only occurred to me recently.”

“Don’t. Please don’t.”

Her voice got trembly: “I can’t understand why I don’t get to do fun things.”

“Mom, you can do all kinds of fun things this summer. Isn’t there anywhere else on Earth you’d like to go — literally anywhere other than the exact place where you knew I was going to be?”

“No, Josh, there isn’t.”

Now I was stamping my foot on the narrow little room’s thin carpeting. I could feel the hard cement underneath it. No one could hear me. No one would ever know my agony. What happens in New New Quad stays in New New Quad.

“You. Just. Cannot. Go. To. Naropa.”

Ultimately, she relented.

I hung up the phone, feeling drained and a bit guilty. Was I standing in the way of Mom’s happiness?

No — this was my adventure! I picked up the phone’s receiver and began to dial Nina’s number in Boulder. I would be the only member of my family spending that summer at Naropa. I’d learn some more about acting, and maybe about being. Hell, perhaps Mom was right — and Chögyam Trungpa would even have something to teach me about breathing … and those tensions in me might begin, ever so slightly, to dissipate.

Re "I wasn’t just a virgin, I was kind of a super-virgin"... having seen Red Diaper Baby, I beg to differ on this. ;-) (I actually got out my copy of your book to check the chronology on this...)

Can't wait to hear how it went.....:)