“Sir, I want to go to the front to fight the fascists!”

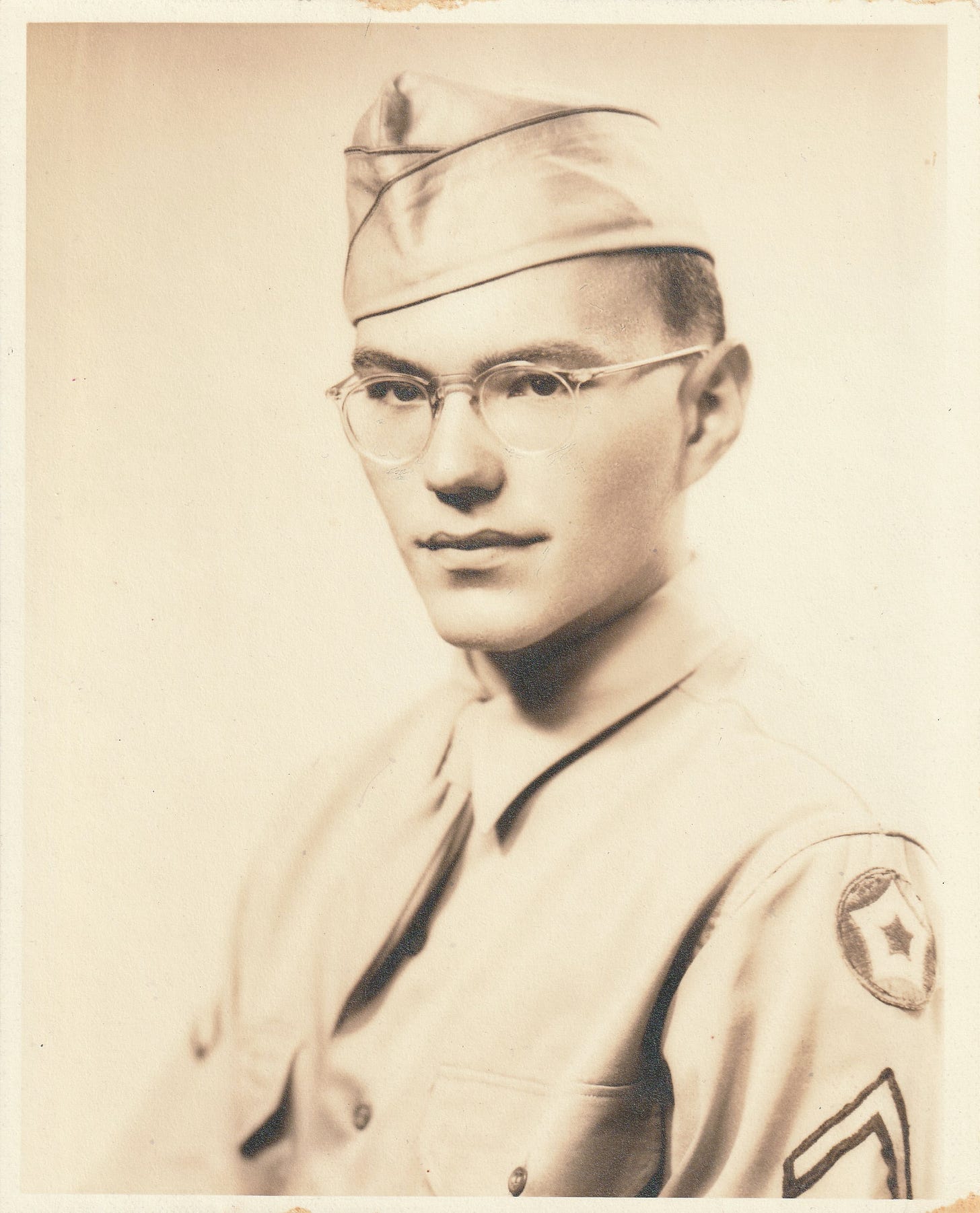

“Son,” the sergeant told Paul, the young man who would later become my father, “your mathematics score on the Army entrance exam was through the roof. We’re assigning you to Intelligence.” This was during the Second World War.

After they’d trained Paul for a year and were ready to put him to work, Intelligence ran a pro forma background check on him. That’s when they found out he was a highly active member of the Young Communist League. So that was that for Intelligence.

Once again, Paul found himself standing before the sergeant. “Sir, I want to go to the front!” he told him.

“I am not sending a nice Jewish boy like you to the front!” the sergeant said. He told Paul that he would now be fixing phone lines.

Paul found that he enjoyed climbing telephone poles. Years later, he told me the key to surviving that job, should I ever be hired to do it: “Never bend your knees, my son.”

But not fighting the fascists ate at him. So one day he went back to the sergeant.

“Sir, please! Send me to the front!”

The sergeant partially indulged my father by sending him, not to the front, but to France. There, Paul and other soldiers who were highly proficient in math were given a crash course in engineering. They were served fine French food and wine, and generally lived a cushy life. Every month, a high-ranking officer would come and give them a rousing pep talk, which always ended: “And if any of you don’t like it here, we can always send you to the front!” After about six months of villa life, Paul, annoyed that a fellow soldier had cheated off of him on a recent exam, stood up and announced, “I want to go to the front!”

So they finally agreed to send him to the front, in the Philippines. At the start of the boat trip, Paul found that he was one of the few onboard who weren’t getting horribly seasick. He tried to teach others his coping technique, which was to keep his knees always bent, so he could adjust to the back-and-forth rolling of the ship. Years later, he told me, should I ever find myself in a similar situation: “Always bend your knees, my son.”

(As you might imagine, I began to feel some confusion regarding the plusses and minuses of knee-bending.)

Later on that sea voyage, Paul began teaching Mandarin to some of the other soldiers — undaunted by the fact that he himself could not read or speak the language. It was hard for him to drum up students, as most everyone was busy being miserable and throwing up. In fact, morale was getting lower and lower: there was sporadic fighting breaking out everywhere on the ship. He also led a small Marxist study group, in the process radicalizing a formerly gentle fellow named Mo Krantz. At one point, as the mess hall exploded into a full-fledged riot, skinny Mo got up on a table and yelled: “Comrades, comrades — let’s look at all this dialectically!” Fortunately, Paul was able to haul his student off the table and away from trouble before he could get pummeled. (Paul and Mo would remain lifelong friends.)

As the boat finally approached the shore of the Philippines, armistice was declared. So Paul never got the Army job he’d longed for: at the front, fighting the fascists.

Back in the States, Paul once was hired to be an ice-skating instructor at a rink in Central Park. He didn’t mention on his application that he had never ice-skated before. The key, he decided beforehand, was to keep his knees constantly bent. (Hey, it had worked on the boat!) His first day on the job, a woman beginner beckoned for him to come over and teach her how to skate. Wobbly on his own skates, he bent his knees and slowly made his way across the rink. Very slowly. So slowly that not only the woman, but all the other skaters, as well as his supervisor, ended up watching him will himself forward, inch by painstaking inch. Before he could reach the woman, he’d been fired.

He sold ice cream for a while. There was a bit of subterfuge involved — though the ice-cream store advertised several flavors, in truth there was only one. His boss told him: whatever flavor people order, tell them that’s what you’re giving them. I’m trying to imagine how this might have succeeded. I guess if the flavors were, say, vanilla, peach, lemon, pineapple, and coconut, and if the ice cream was, say, beige, maybe you could make this work visually. He told me that it was a peculiar flavor, one that didn’t really taste like anything specifically. Ultimately, though, he felt honor-bound to reveal the truth to prospective customers, and he was asked to move on.

Eventually Paul got his Master’s in Special Education from NYU and began teaching in a public school in Manhattan. He noticed that his students tended to favor snack foods like potato chips and sugary drinks like Coca-Cola, so he decided to devise a scientific experiment to show them why they should change to a healthier diet. He got two rats and put each one in a cage. He fed one rat only potato chips and Coke. The other rat got meat and milk. The meat-and-milk rat died, and Paul’s students went home to tell their parents that Mr. Kornbluth had scientifically proved to them that they should live on junk food. So that’s how that job ended.

When I was little, my dad was in a particularly down time, economically. He washed dishes. He worked as a mover (“Always bend your knees, my son!”). He temped as a typist. Sometimes he sold his blood plasma.

Eventually he got a gig teaching Special Ed at a middle school in suburban Stamford, Connecticut. He enjoyed teaching his students to play the piano — which, as you may guess, he did not himself yet know how to play (he always stayed one lesson ahead of them). It was there that he met another teacher named Sue Kover, who came from a tiny Midwest farm town, and when they eventually got married and began having children together he realized that he needed to start holding on to his jobs. And to his great credit, he did. In fact, like many other public-school teachers, he took on second and third jobs.

For some time, at nights he worked the cash register at a liquor store near where we lived in Washington Heights. He’d often come home with stories to tell. Once an elderly German woman came in and ordered pisswater. My father gently tried to tell this obviously addled person that the store didn’t sell pisswater — and, moreover, that it was generally a bad idea to drink pisswater. But the woman persisted: “Pisswater! Pisswater! Pisswater!” Finally he took her to the back room to show her that they had no pisswater in stock. Indignantly, she pointed to a bottle of … Pisswasser, a German export lager. He actually held on to that job for several years!

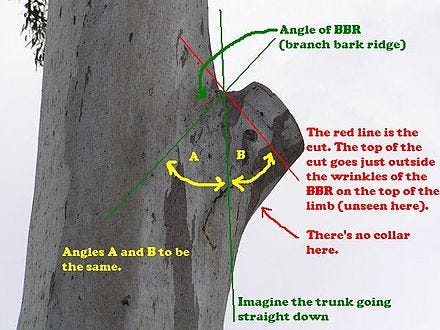

One year, after seeing a help-wanted ad on the teachers’ union bulletin board, he took a summer job as a gardener. This was really cool for me, as it was a live-in deal: my father got to stay in a little cabin on the lovely property of a prosperous Stamford dentist, and Sue and I could join him there. A lifelong Manhattanite, I was delighted to discover fireflies, and ran around at night collecting them in jars. Things seemed to be going great, until one afternoon Dad hurriedly entered the cabin and told Sue and me that we needed to pack up and leave immediately. As we rushed to the car, the dentist yelled at my dad, “If you weren’t Jewish, I’d report you to the teachers’ union!” On the drive back to the city, Dad explained that when the dentist had instructed him to prune his prized apple tree, Dad (whose upbringing in the Bronx had not included any instruction in landscaping) assumed that “pruning” meant cutting off all the branches, leaving only the naked trunk. (Not true, apparently.) In all the tumult, I never got to ask him if he kept his knees locked when he climbed up the tree.

Ultimately — heroically — my father spent the last years of his working life doing a wonderful job as a teacher. At his middle school (which encompassed the seventh and eight grades), he was appalled at how the “lowest” students entering the school — all of them poor — were treated as unteachable. He persuaded the principal to allow him to assemble a team with three other teachers who would take on the “bottom” four entering classes and stay with them through the end of the eighth grade. He said he was going to show that, so far, the only thing these kids had learned in school was that they could not learn. By the end of two years, when his students graduated from the eighth grade, they were reading Tolstoy. Later, after continually flaunting the results of his project to the school authorities, they fired him, citing insubordination. He fought his dismissal, lost his case, and, shortly after that, had a disabling stroke. He never worked again.

One of my father’s firings that I’ve left off of this list is when he lost his job as a social worker for the New York City Youth Board (a job I’ve described in a previous post). The story of that particular firing — which was epic and, in its own way, magical — will have to wait until Christmas (for reasons that will become obvious). But for now: Happy May Day, the international celebration of working people! Always bend your knees, or definitely don’t! And catch those fireflies while you can!

What a great Dad! I'm reading Alan Alda's book, "Never Have your Dog Stuffed" that I learned about from your interview with him - there are similar qualities in the style of these two men. Wonderful to know of them and really enjoying your stories, Josh! Huge thanks, Sara