When I'm out walking

I strut my stuff

And I'm so strung out

I'm high as a kite

And I just might stop to check you outLet me go on

Like a blister in the sun

Let me go on

Big Hands, I know you're the one

That syncopated drumbeat: bum-BUM, bum-BUM. I loved (and love!) “Blister in the Sun,” the opening track on the Violent Femmes’ self-titled debut album. In 1983, the year it came out, I was working as a copy editor at the Boston Phoenix and struggling emotionally with the fallout of my father’s catastrophic stroke four years earlier. It had been his dream (well, one of them; he had many dreams for me) that I become a journalist — though what he’d had in mind was me becoming a muckraking reporter like I.F. Stone or Lincoln Steffens, not the guy who un-split your infinitives and semi’d your colons. When Boston’s legendary Storyville club announced that the Femmes were going to come through in September, I and a bunch of my Phoenix friends got tickets.

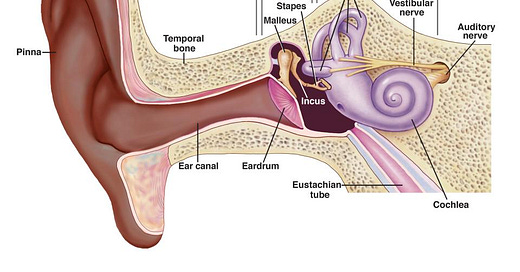

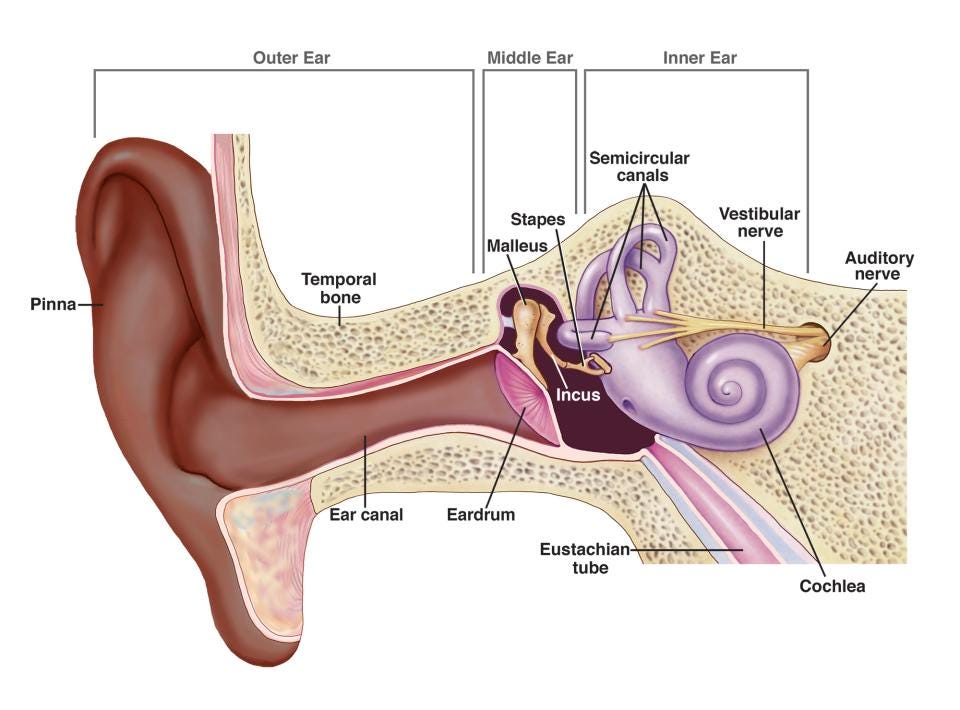

My dad died on Sept. 1. I was grief- and guilt-stricken (I felt I should have spent much more time with him during his long illness), and on the day of the concert, a week or so later, I wasn’t sure whether I should attend. I ended up going — and I remember feeling so damn happy. The Femmes were awesome. I stood right by the stage, in front of a big speaker. I was drinking a Diet Coke with ice (hey, I know how to party!). And then, towards the end of the show, there was a moment — a particularly loud sound, maybe some feedback — and suddenly everything sounded muffled. When I went out to a Chinese restaurant with my friends after the show, that muffled-ness was still there. Several of my Phoenix pals were rock critics, and I’d been their plus-one at much louder concerts than this one (after an Aerosmith stadium show that my friend Doug Simmons took me to, my ears kept ringing for a day or two before going back to normal). So I didn’t start to worry until that muffled quality eventually resolved into a very clear, loud, high ringing sound that went on for a week, and then another week, and another.

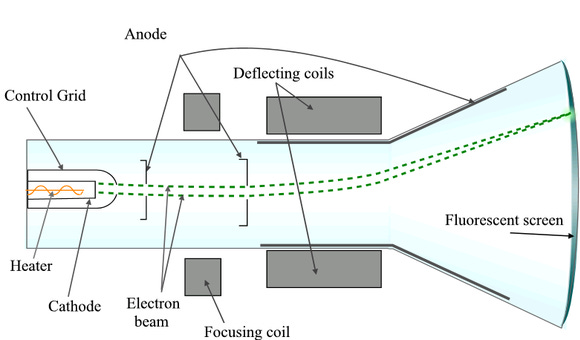

Weirdly, that constant ringing was exacerbated when I sat at the computer terminals on which we did our editing. These had CRT (cathode-ray tube) monitors, and for some reason whatever had gone kablooey with my ears had made me painfully sensitive to a sound they emitted that some people didn’t hear at all and others (including me, before that concert) perceived as a very faint, not unpleasant high twinkling. Now they sounded to me like super-amplified dentists’ drills, and they also made me feel an intense, painful pressure inside my ears. I encountered the same issue when I watched TV — which was bizarre, as the little bit of writing I did at the time was as a TV critic.

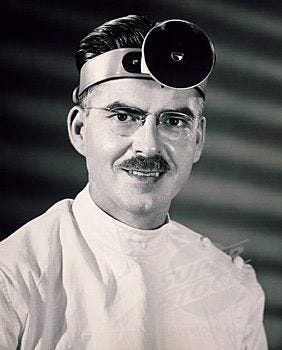

After a month or so of this, I went to see a doctor at Mass General. After I’d waited for a while in a little room, he strode in. His manner was brisk, impatient. He was wearing one of those round mirror thingies on his head. I told him about the ringing in my ears. “Yeah,” he said, matter-of-factly. “You have tinnitus.” (Like others I’d encounter in the medical profession, he pronounced the word with the stress on the first syllable — “TIN-i-tus” — unlike how most people say it: “tin-EYE-tus.”)

“Will it go away?” I asked. I was trying to keep my voice from shaking.

“Probably not,” he said. “The longer it lasts, the more likely it is that it’s permanent.” He checked his watch. “Look,” he said, “we all have our cross to bear.” And he strode out. The entire appointment couldn’t have lasted longer than five minutes, tops.

Over the next two years I tried all sorts of supposed miracle cures. I sipped an herbal tea that had the taste and consistency of primordial ooze. I wore a mouthguard at night in case the problem was TMJ (temporomandibular joint) disorder (it wasn’t). I had my wisdom teeth pulled and all my fillings replaced, as recommended by a guy my mom had heard on WBAI-FM. I saw a hypnotist. Nothing stopped the ringing.

So I waited. And waited. Waiting for my tinnitus to stop became the main thing I did. Until one day I snapped.

At the Phoenix we copy editors (I was one of two — hi, Scot Lehigh!) had a particularly tough turnaround late in the week. The news section went to bed as late on Thursday night as possible, so the news would still be fresh when the paper came out on Friday afternoon. We did our copy-editing into the wee hours, then went home for just a bit of sleep before staggering back into the newsroom on early Friday morning to proofread the news section so the entire issue could be brought to the printer.

Well, one Friday morning, sleep-deprived as usual and super-stressed by my tinnitus, with the whining and the pressure piercing into my noggin, I just lost it — and in the middle of the Phoenix newsroom I let out a tremendous scream. For a while now, I had been messing up at work, coming in late, calling in sick, and generally being a fuck-up. Now, as everyone stared, one of our editors, the late (and much-beloved) Clif Garboden, grabbed my arm and pulled me to the elevator, then accompanied me down to the street, eventually depositing me in a used bookstore around the corner before he headed back upstairs to discuss my situation with the other editors.

I remember standing among the dusty stacks as I awaited my fate. There have been times in my life when I’ve had this thought: This is happening now. Up until the tinnitus began, I had been a terrific copy editor: dependable, passionate about helping to make the work of “my” writers the best it could be, and oh-so-anal. Looking back, I’d earlier reached the pinnacle of my copy-editing career on one (pre-tinnitus) Friday morning, when, while proofreading the tiny, nine-point type that the Phoenix insisted on using, with a yucky typeface that was extra-hard to decipher, I noticed that the period at the end of a sentence was in italics. My main supervisor, managing editor John Ferguson (also beloved, also gone from this world too soon), was astonished: how could I tell? At that size, it can be hard to discern a period from a comma — much less determine that the period is italicized! But I was in The Zone. I imagine that Michael Jordan felt much the same way when he dropped in that championship-clinching jump shot over Bryon Russell of the Utah Jazz to clinch the 1998 NBA championship for the Chicago Bulls.

Anyhow, Clif came back down a while later to bring me back up to the newsroom and face my bosses. They told me to take some time off. I did, but things didn’t really improve. I continued to struggle with my job — and with what I look back on as my first extended bout with depression. My father was gone, and my journalism career had imploded.

Somewhere in those dark times after I’d left the Phoenix, after so many frustrating appointments with so many specialists in my futile quest to find a cure for my tinnitus, I went to see yet another: an ear-nose-and-throat doctor in nearby Brookline, Mass. When I entered his office, I noted an unusual feature — an ornamental water fountain, like one you might find in a fancy garden. I went through my usual recitation: the Violent Femmes concert, the brief period when everything sounded muffled, and then the endless ringing.

He said, “Josh, I’m going to ask you to do something. It’s what I ask of all my patients with chronic tinnitus. I want you to send me a card every year around the holidays, and just tell me how you feel about your tinnitus. What I find with my patients — virtually all of them — is that, year by year, they are doing better with their tinnitus: it’s become less and less of a problem for them.” He added that he, too, had tinnitus. He’d found that the sound of running water helped to mask it. Thus the fountain.

Leaving the doctor’s office, I initially felt my usual disappointment: another expert had failed to cure me. But as I stood at the bus stop outside the building, it was as if a profound weight had suddenly been lifted off of me. In that moment, I stopped waiting for the ringing to go away. The ringing simply was. And with the tinnitus no longer being my nemesis, I simply was, too. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I had just begun the lifelong process of learning to become myself.

Not long after that, as we walked together near the Phoenix’s offices, my friend Scott Rosenberg (then a theater and book critic at the paper) asked me: “If you could do anything for a living, what would it be?” and to my absolute surprise I immediately replied, “I’d be a stand-up comedian.” Within a week, I did my first open-mic bit at a comedy club called Stitches: I bombed, but it didn’t really matter. I loved being up there on stage, in front of a live audience! A year or two later Scott brought me to see the autobiographical monologuist Spalding Gray, and discovering this great artist, and the art form he spearheaded (not standup, which is joke-driven, but the telling of long, elaborate stories in a theatrical setting), got me on the path to my own monologuing career — in which I’ve told stories about seemingly everything in my life … except my tinnitus.

It’s been a long time since that 1983 concert at Storyville led me, through a sometimes arduous process, to becoming a professional storyteller — to inhabiting, if you will, my own storyville. Throughout, the ringing in my ears has persisted — sometimes louder, sometimes quieter, always there. Usually, it doesn’t bother me (though to be honest, sometimes I still struggle with it). At this point, it’s part of who I am. I wouldn’t have become a monologuist if not for the tinnitus — I’m sure of that. And if I hadn’t become a monologuist, then Sara, the love of my life, wouldn’t have seen me perform at Fort Mason in San Francisco, and we wouldn’t have met in the parking lot outside the theater. And then we wouldn’t have had our beautiful son. When our boy was little, as we all listened in the car to “Good Feeling,” the gorgeous last track on that debut album by the Violent Femmes, I told him that the greatest happiness of my life was all due to going to hear this band.

Yup, most musicians I know deal with some version of Tinnitus. I went to a "chiropractor" that did some kind of energetic touch or something and for a brief moment or two the wrangling calmed down. Lovely, but he charged so much for sessions that I decided to just accept it - as you say, "It just is." If I'm listening to something else, I don't notice it as much...thanks for another sweet story, Josh!

My tinnitus appeared around Christmas when covid finally got me. The covid passed quickly, one tough day, but the drone stayed. The ENR doc shrugged off the covid explanation with maybe-hard-to-tell. After hearing tests and an MRI, no explanation or treatment emerged. Slayer, Guns N' Roses, Metallica, AC/DC, Ramones, Aerosmith (sorry 'bout that) et al are decades gone though probably dinged the ear bones. Knowing there's nothing to be done has made the buzz more tolerable. Hardly notice it now, except if I wake in the middle of night. Silence brings out the worst of it.