Dad's 1st Letter Home: Joy & Exhaustion in Georgia

Continuing to explore the mystery of his total break with his parents.

Last week I wrote about a great mystery in my family history: Why did my late father, Paul, and his parents, Julia and Fred, turn so irrevocably away from each other? A packet of letters that he wrote to them starting in the late ’40s, saved (improbably) by Grandma Julia and then passed along to me by my cousins, offers some tantalizing (and heartbreaking) clues. As I read them, I feel utterly bifurcated: He will always be “Dad” to me, but he wrote these letters when he was in his mid-20s — a decade before he became my father, and (as it happens) the age my son is now. I feel utterly protective of the young Paul who wrote these letters — and so proud of him as well! I only wish my grandparents had felt the same way.

Along with that bifurcation, I also feel a powerful sense of immediacy: Although Paul went down to Georgia in 1948 to support the ultimately unsuccessful presidential candidacy of Henry Wallace (a staunch progressive, not to be confused with the segregationist George Wallace), he stayed there to continue fighting for voting rights — and here we are today, with the battle for voting rights in Georgia, especially for those of Black citizens, at the very center of our national politics. So there’s a political storyline to this correspondence as well as a personal one.

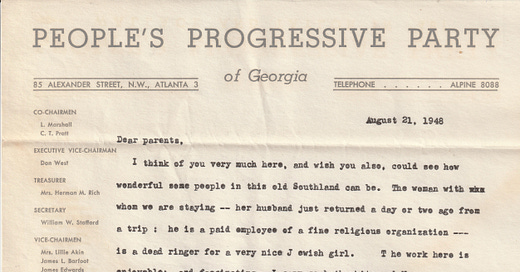

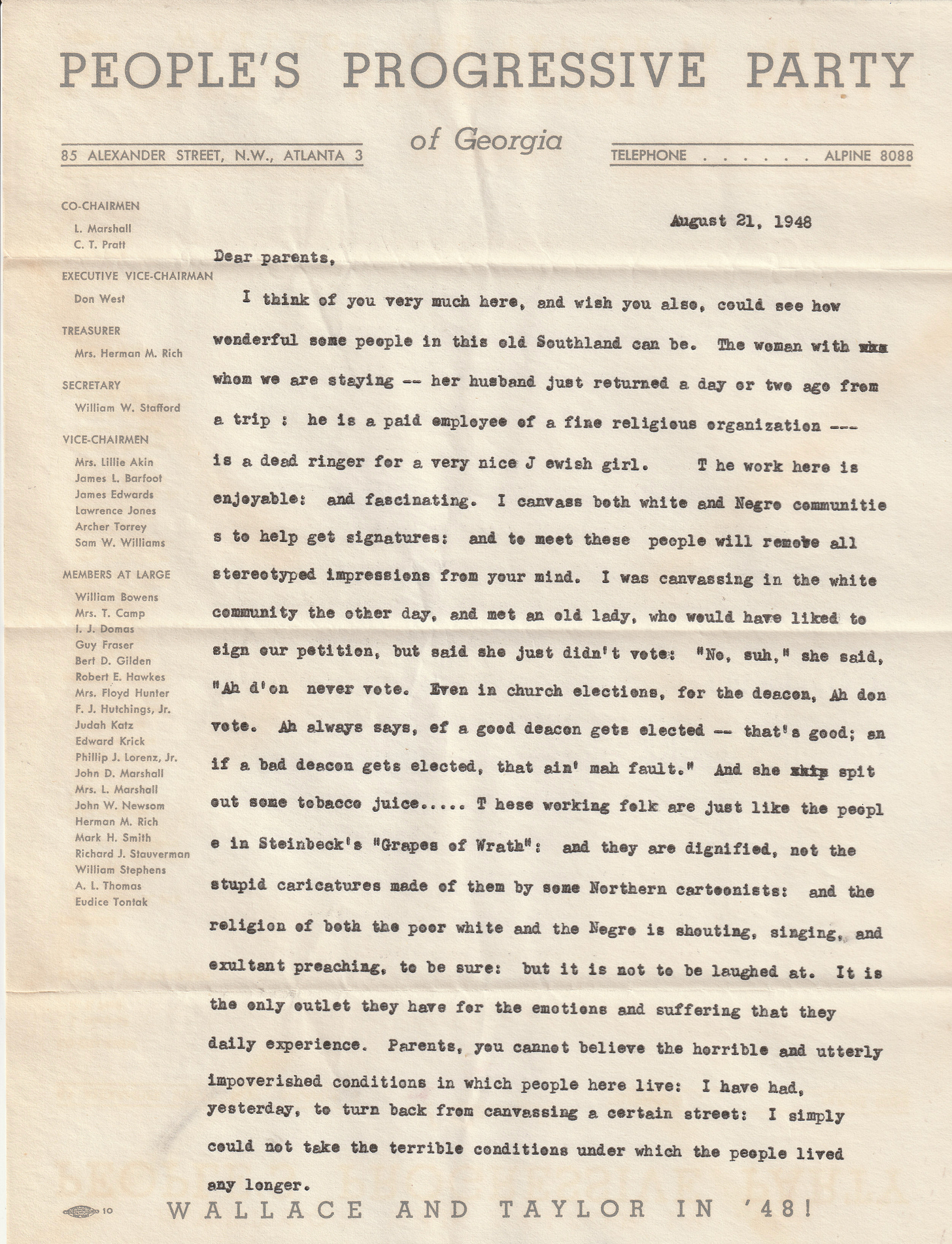

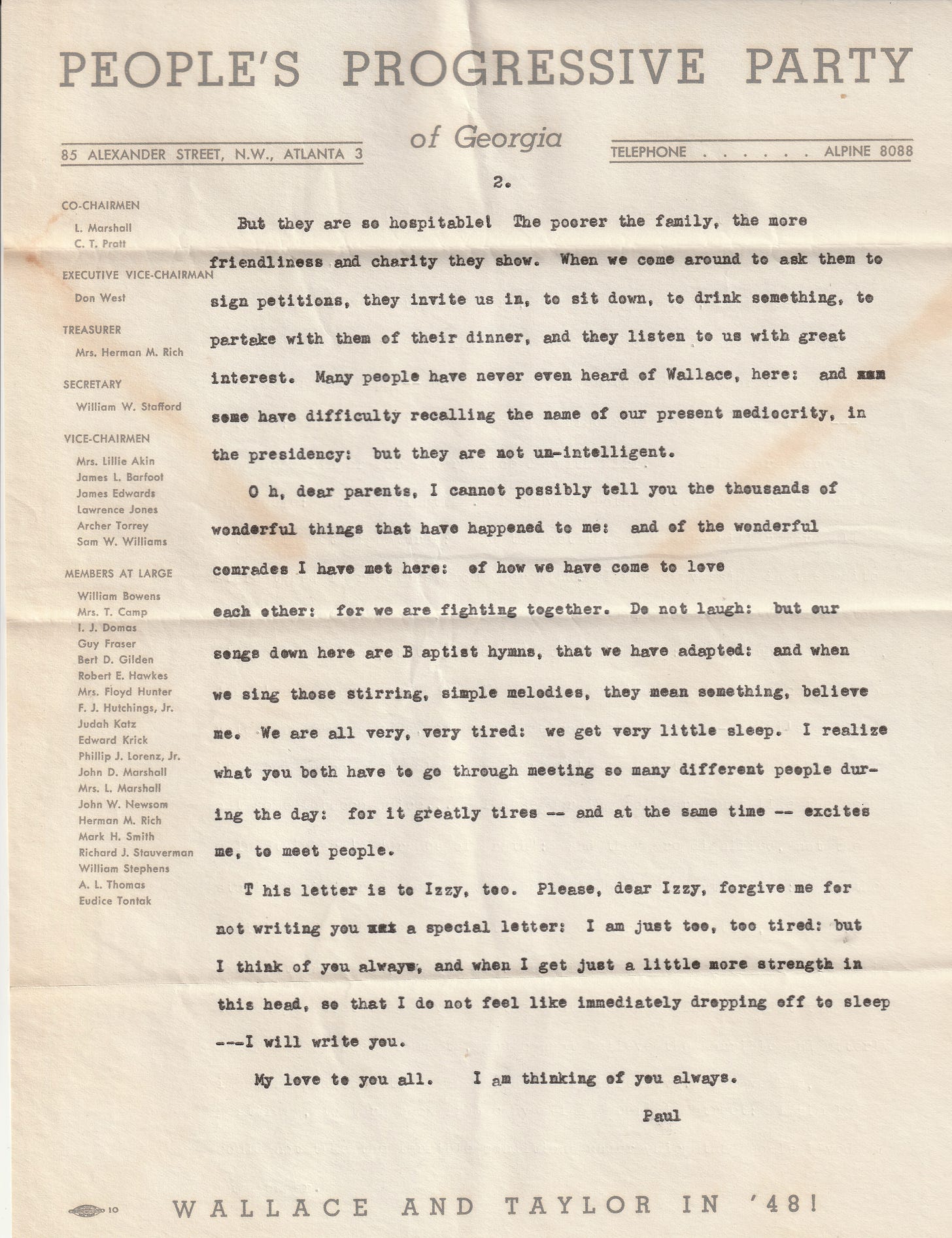

The first letter, from Aug. 21, 1948, is on the letterhead of the People’s Progressive Party of Georgia. When I Googled this party, I found an article in an academic journal called Phylon — founded in 1940 by the great writer and thinker W. E. B. Du Bois at what is now called Clark Atlanta University (and still being published). The article — from the Fall 1949 issue — is by Samuel Woodrow Williams, himself a distinguished scholar as well as a Baptist minister, who was an influential figure in the Civil Rights Movement. It offers a thoughtful critique of the party, which, according to Williams, “never exceeded in total statewide membership more than two hundred” before (apparently) dissolving. At a time when lynchings were rampant and the Ku Klux Klan found “healthy pasturing in the state,” and when the Democratic Party in Georgia was thoroughly racist, there would seem to have been a crying need for an interracial party like the People’s Progressive Party. But, Williams notes, whites feared the ramifications from other whites for being associated with Blacks. And — this also rings a very contemporary note — the existential threats to Blacks’ lives and safety were so enormous that they felt they couldn’t afford to support a party that was dedicated to Wallace’s underdog campaign against incumbent Harry S. Truman.

Williams writes:

They could not see any value to them in voting for a candidate who was going to lose anyway. Negroes do not see why they should waste a vote when they have so much to fight for with their vote. Their immediate needs in terms of decent treatment as American citizens are so great that they cannot postpone them by protest voting. Negroes felt therefore that to vote for Truman was the wisest and surest vote they could cast in 1948.

So it was a complex situation faced by the political party that Paul was working for at the time of this first letter, when the election was still months away. And, in our great family tradition, their immediate cause — a Henry Wallace presidency — was doomed. But I see a young man from the Bronx dealing in a nuanced way with his sudden immersion in the segregated South. Paul writes:

The work here is enjoyable: and fascinating. I canvass both white and Negro communities to help get signatures: and to meet these people will remove all stereotyped impressions from your mind. I was canvassing in the white community the other day, and met an old lady, who would have liked to sign our petition, but said she just didn’t vote. … These working folk are just like the people in Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath”: and they are dignified, not the stupid caricatures made of them by some Northern cartoonists: and the religion of both the poor white and the Negro is shouting, singing, and exultant preaching, to be sure: but it is not to be laughed at. It is the only outlet they have for the emotions and suffering that they daily experience. Parents, you cannot believe the horrible and utterly impoverished conditions in which people here live: I have had, yesterday, to turn back from canvassing a certain street: I simply could not take the terrible conditions under which the people lived any longer.

In the second (and last) page of the letter, Paul describes the friendliness and warmth of the poor people he’s been canvassing. And then he goes into a practically ecstatic description of all that he’s been experiencing in Georgia. The tone reminds me very much of my father as I’d know him in decades to come — when he’d wax poetic about “the people,” especially the poor and downtrodden, and about those aligned with him in the struggle for justice. This love was totally genuine — and, I now believe (especially after going through the rest of this correspondence), in stark contrast with what he got back from his parents, whom — in these letters — he keeps reaching out to, hoping to elicit from them an emotional connection with his cause, with his fellow activists, and, ultimately, with him:

Oh, dear parents, I cannot possibly tell you the thousands of wonderful things that have happened to me: and of the wonderful comrades I have met here: of how we have come to love each other: for we are fighting together. … We are all very, very tired: we get very little sleep. I realize what you both have to go through meeting so many different people during the day [ed. note: is this a reference to Grandma owning her clothing store?]: for it greatly tires — and at the same time — excites me, to meet people.

He follows this with a message to his little sister.

This letter is to Izzy, too. Please, dear Izzy, forgive me for not writing you a special letter: I am just too, too tired: but I think of you always, and when I get just a little more strength in this head, so that I do not feel like immediately dropping off to sleep — I will write you.

I am thinking now of my Aunt Izzy and her gap-toothed smile that, after their deaths, reminded me so much of both her big brother and their mother. She kept up the connection with Julia and Fred, whom she acknowledged to me as being “difficult.” Whereas my dad became consumed with a white-hot hatred for them, cutting off all contact. Clues about where it all went wrong will emerge later in this correspondence. I also suspect the influence of a therapist whom my father came to rely on: Saul Newton, who would go on to lead a paranoid, anti-family psychoanalytical cult called the Sullivanians. (More on that in a future post.)

But for now, to try to regain a temporary sense of peacefulness within my own soul, I prefer to dwell on the seemingly untroubled, utterly anodyne closing words of this first letter:

My love to you all. I am thinking of you always. Paul

What an excellent human, your Dad was, Josh! I second the comment from Jeanne, these memories need to be shared - in a book! The never ending "good" fight continues on all levels. Thanks again for what you do.

Ya gotta publish this story in a book when you’re done!! You’re a brilliant writer!!!