Well, he tried!

That’s the first thought that occurs to me as I look through this little booklet that my father, Paul, set up for me in 1968, when I was nine years old. I do recall that I had a lot of trouble motivating myself to practice my violin. It didn’t help that my mother, Bunny, who had me most of the time, would frequently show up in my bedroom doorway, while I was practicing, and — squeezing her hands over her ears — scream the words, “Squeak squeak squeak squeak squeak!!!” Though to be fair to Mom, I didn’t practice much more than that when I was over at Dad’s. Nor did he usually have to hear me playing. Making a pitifully small amount as a public-school teacher, he’d often be away at his second job, behind the counter at a liquor store, or at his third job, typing statistical documents at a bank. (Did the bank know he was a Communist? It probably didn’t matter, so long as he got the numbers right.)

Dad had possibly been getting word from my violin teacher, a woman named Jerre Gibson, that I hadn’t been making much progress on the instrument. Or maybe Dad’s girlfriend, Sue, had mentioned that, despite my promises to start practicing regularly, she hadn’t heard any actual music emanating from my room. As I recall, in those days I spent a lot of my time making jewelry out of pennies on the little kiln that Dad had gotten me. I’d spend hours melting colorful goopy stuff onto pennies, waiting for them to cool off, then presenting my latest homemade trinkets to Sue — who must have amassed a ginormous collection of penny-charms. She always thanked me profusely, with great Midwestern politeness.

In any case, Dad decided to get proactive about my lack of practicing — thus this booklet. On the inside of the front cover, he left me contrasting messages, one with encouragement and the other with a note of caution:

My father probably knew that quoting Josh White would carry particular weight with me, as we listened to that great, progressive folk singer’s records a lot — and Dad had once mentioned a dream he had: that one day he and I would tour together as a folk-singing duo, like Josh White and his son, Josh Jr., whose age gap, according to Dad, was exactly the same as between him and me. You may wonder (as I do a bit, myself) why, if that was a dream of my father’s, he placed such emphasis on my training as a classical musician — rather than, say, encouraging me to practice the guitar.

I think the truth was that, in our family, playing folk music was just something you did — like breathing, or plotting to overthrow the U.S. government — whereas playing classical music was something you were meant to aspire to (and, thus, suffer for). In fact, Mom and Dad had met when — as undergraduates at the City College of New York (which was, at that time, where pretty much all the city’s Jewish Communists got their higher education) — they had independently been booked to sing a few folk songs at the same political rally for Puerto Rican independence. By Dad’s own account, after he passionately sang several songs in Spanish, the rally’s Puerto Rican organizer thanked him profusely and then politely inquired: “Tell me, what language were you singing in?”

As for my mom, she had attended Music and Art High School, where — because she was relatively tall — she was assigned to play the double bass. She remembered the hassle of lugging around her bass on crowded city buses — and had, for that reason, warned me against it when I was picking a classical instrument. It is only occurring to me at this moment, for the first time in my life, to wonder whether Mom’s mom, my Grandma Dora, gave her grief when she practiced her bass (what’s Yiddish for “Squeak squeak squeak”?). Sometimes Mom seemed to see me as a painful reminder of what she hadn’t gotten as a child — the knowledge of being loved unconditionally, of being adored. Which is what I received from my father pretty much all the time — and which made those few occasions when he seemed even the slightest bit critical, such as when he expressed disappointment that I hadn’t been practicing my violin, such a big deal to me.

In August of that tumultuous year of 1968, I was about to make the transition from my local public school, P.S. 128, to the Cathedral School of St. John the Divine, which I’d be entering in third grade on a choir scholarship. My parents had jointly decided to make this switch after I’d repeatedly been bullied in second grade — culminating in a classmate laughingly locking me in a maintenance closet. Unwittingly, he’d slammed the hinge of the door on my pinkie, fracturing the tip. (“Doctor, will I ever play the violin again?” “Sadly, yes.”) Now, instead of walking a few blocks to school, I’d have to take the No. 4 bus for about 40 minutes each way.

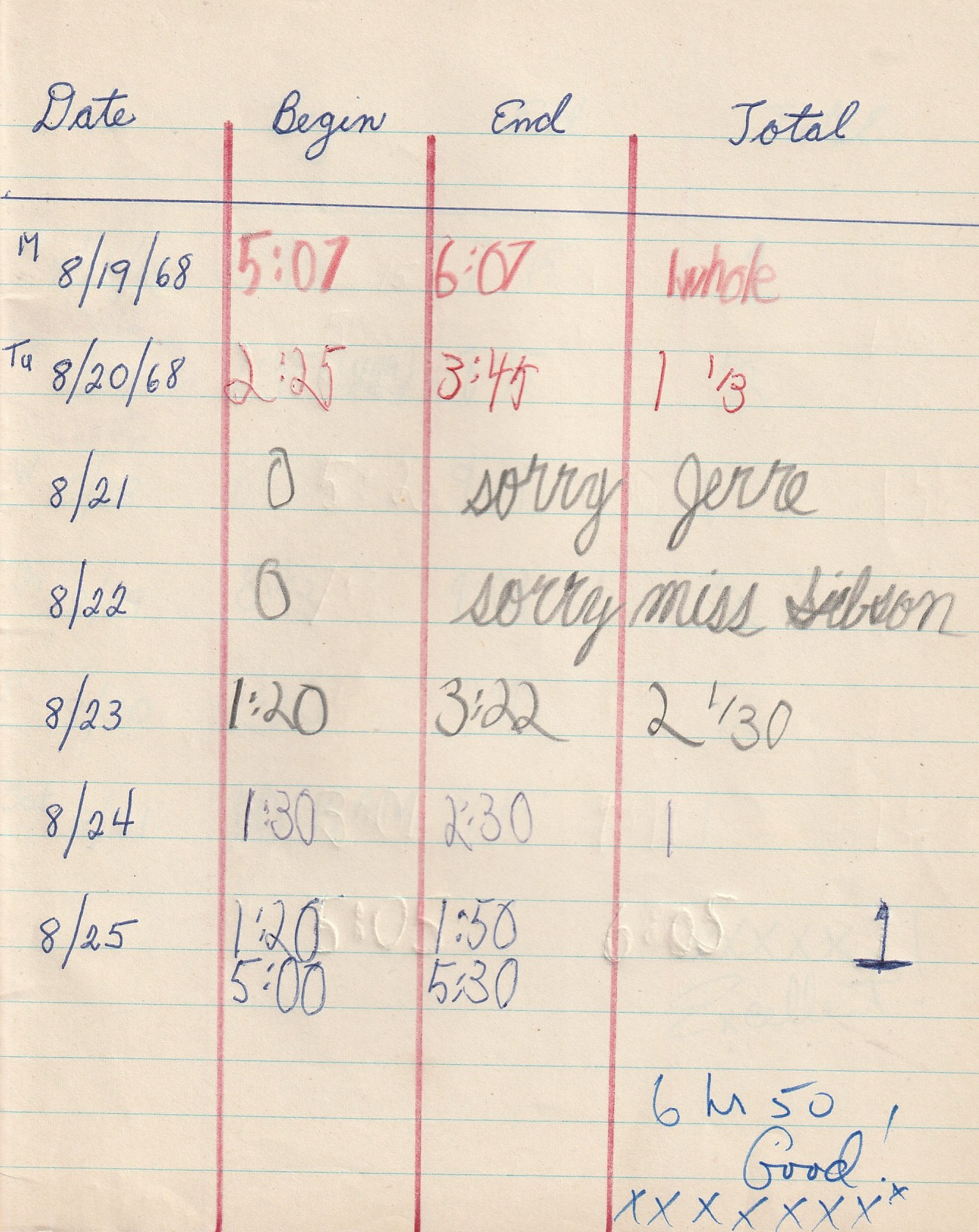

I remember feeling kind of like a failure — I mean, how much of a fuckup did a Communist kid need to be to have to get sent to private school??! So I really didn’t want to mess up with my violin-practicing. And it looks like I did quite well that first week. The next week, however, betrayed signs of slippage:

It looks like Dad had me show my practice log to my violin teacher, Jerre — who totaled everything up and kindly commented, “Good!” But it must have stung me to have completely failed to practice on the 21st and 22nd — as can be seen by my written apologies to my teacher in both entries. I remember really liking Jerre. She lived and taught in an apartment near Columbus Circle. Dad would bring me there on the subway — usually taking a moment, as we walked past the Columbus Monument, to note its strong resemblance to a penis.

For my ninth birthday, Jerre had given me my very first comedy record, The Smothers Brothers at the Purple Onion, which I loved and played over and over — many more times, truth be told, than I listened to any of my records of violin music. (R.I.P. to the great Tommy Smothers.) So indirectly, though I ended up washing out as a violin student, she may have helped to inspire my later forays into comedy performing.

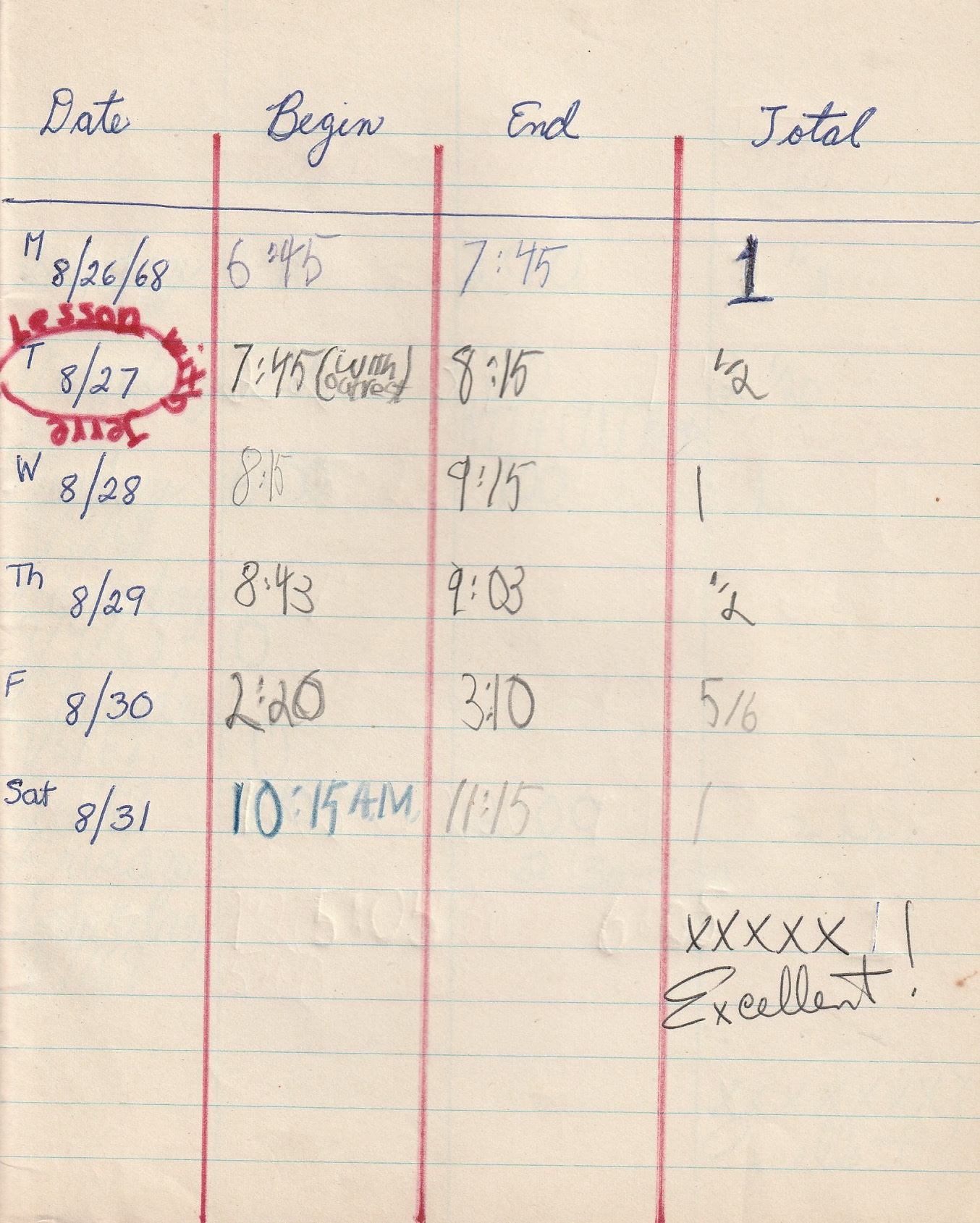

I kept up my faithful reporting on my violin practices for another week:

And yet another:

But then, on Sept. 10, 1968, my brief shining moment of being held accountable seems to have come to an end:

The rest of the pages of “Joshua’s Violin Practice Time-Book” are blank — and I think the truth is that, for me, it was getting close to the time (to paraphrase 1 Corinthians 13:11) to put away violin-ish things. Soon I’d be beginning my studies — and twice-daily rehearsals, not to mention copious services — at an Episcopalian choir school.

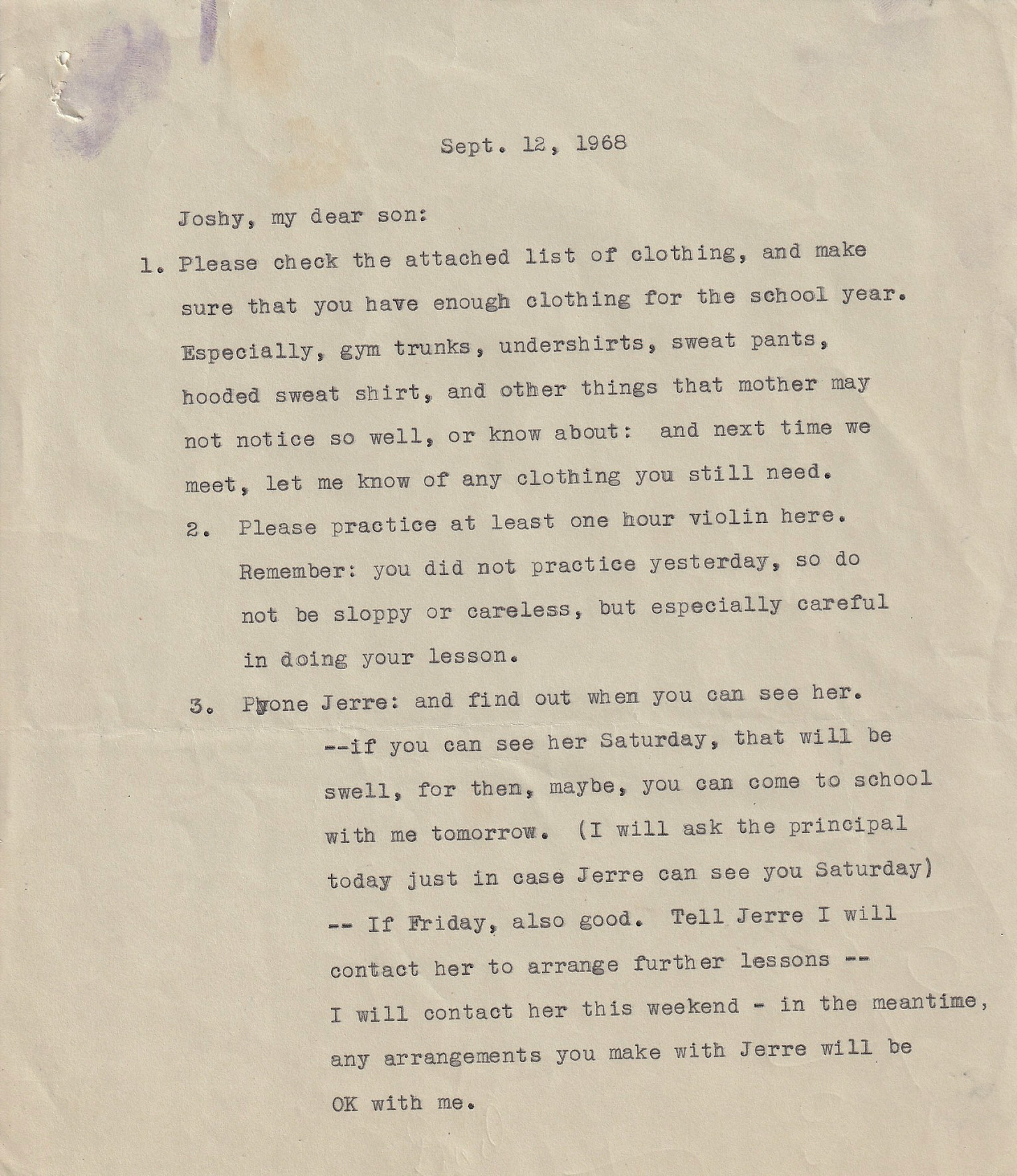

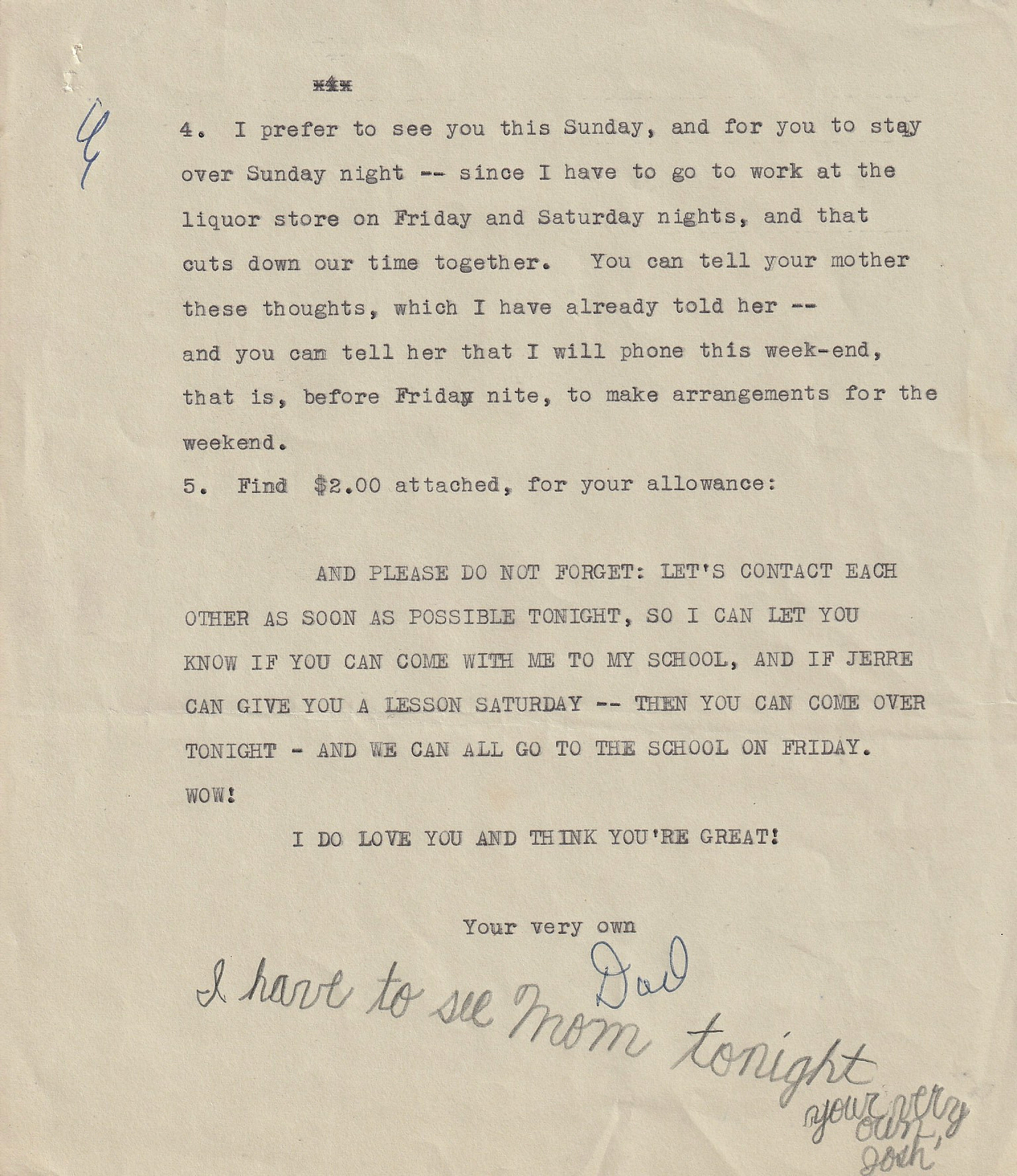

I find it moving to reread a typed note to me from my father, dated just two days after that last entry in the practice book:

Seeing my short, handwritten reply to him on the bottom of the second (and last) page, I have the sensation of being once again in dialogue with him, as if he were still alive and I were still his little boy:

I am also moved to read his final sentence, in all caps: “I DO LOVE YOU AND THINK YOU’RE GREAT!”

Because I always knew he felt that way about me. Even if I didn’t always feel that way about myself.

It’s an incredible gift — one that I still carry, deep in my bones, at the grand old age of 64 (five years past the age that Dad was when he died): to have been loved so fully, from so early, that (even through bouts of depression and all the other tsuris that life can throw at you) I have remained buoyed by this knowledge — I am loved. Listening to all those sermons as a choirboy, about how Jesus loved us, it always made total sense to me that people would crave this feeling — if not from their families, or from society at large, then at least from … Someone.

I think I was wearing my Cathedral School uniform in this little photo-booth picture of Dad and me:

I look like I’m proud of myself. Not a failure as a violinist. Not a failure at all.

Beautiful piece! Your father's lovefor you and yours for him illuminate every word.

A fun read, Josh. Reminded me of some of my childhood memories albeit not with a non violin 😊