My Cousin Cyril

How a late, great science-fiction writer helped pull me out of my recent depression.

I am — blessedly — now recovered from the depression that dragged me down into the emotional depths for several months. Many thanks to my family, my friends, my therapist — and you, my dear readers, who have been so supportive and empathetic! I’d been reluctant to write in this space about my depression as it was happening: so much easier to describe traumatic experiences long after the fact, when you can massage them into a story that you can control somewhat, that makes sense of the suffering — that can hopefully show how it led to a breakthrough in self-understanding. But when you’re lost in it? Hopelessly lost? When you don’t know whether there will be an uplifting ending? When you don’t know if it will ever end? It was scary to send out these missives — but also, ultimately, cathartic. Each time I hit “Publish” — always after a period of queasy self-doubt — something inside of me, the scared little boy I still harbor, even after 65 years of diligently striving towards manhood, moved incrementally closer to that elusive sense of agency.

There was a moment, as I felt myself sinking into what I feared would be my first depressive episode in years, when I suddenly flashed — out of nowhere — on a long-ago film project that had never come to pass. Nearly 20 years ago I used to hang out with the great writer Jonathan Lethem (I forget how we met — maybe he came to one of my shows?). And one day he was talking about how much he loved the work of the late science-fiction writer Cyril M. Kornbluth. I told him that Cyril was my father Paul’s cousin, and that I’d always been proud to be related to him. Proud, but also bummed — because Cyril had died at the early age of 34, in 1958, the year before I was born. He’d been running for a commuter train in Levittown, New York, late for an interview to become the editor of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, when he had a fatal heart attack. It’s always been a hole in my life that I never got to know him — especially given how tragically fractured the Kornbluth side of my family was, and thus how little I knew of most of them.

One day Jonathan told me he had an idea for a movie involving Cyril, and he was wondering if I’d like to collaborate with him on it. Half of it would be kind of a documentary, exploring Cyril’s too-short life. He was a quirky dude. By many accounts, he never brushed his teeth, which eventually turned green — a source of such embarrassment for him that he kept his hand over his mouth when he talked to people. He detested black coffee, but still drank it as (according to one account) “he thought that it was the holy obligation for all professional writers.” (True.)

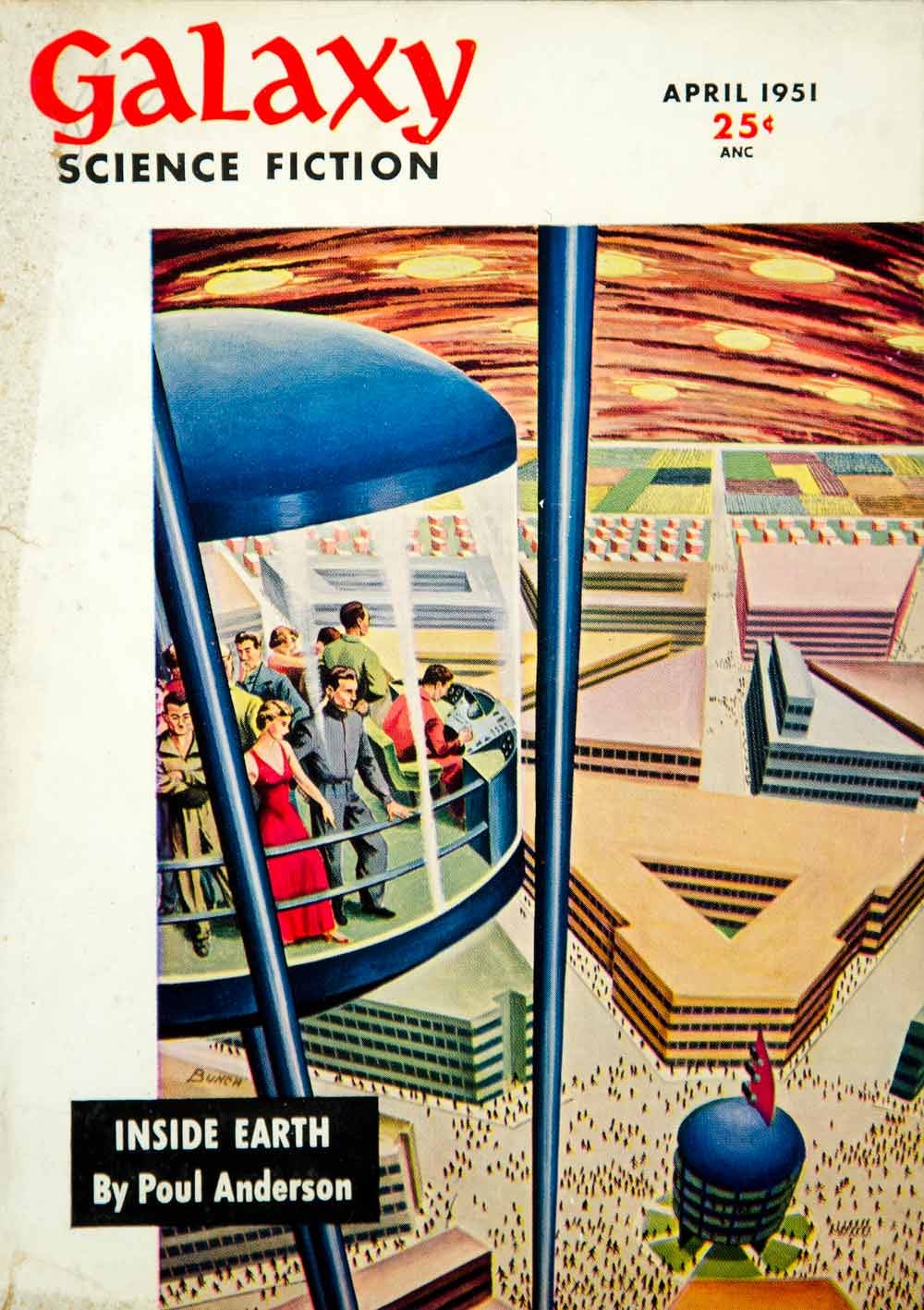

Maybe all that coffee had something to do with it, but he was also amazingly prolific, publishing his first short stories when he was a teenager and sometimes contributing several tales to a single edition of a magazine, under some of his dazzling array of pseudonyms.

He wrote a ton of stories and novels by himself (“himselves,” given his numerous pseudonyms?), and many others with collaborators, notably Frederik Pohl — who completed many of Cyril’s unfinished stories after his death, including “The Meeting,” which won a 1973 Hugo Award. Pohl had been, along with Cyril, a member of a remarkable group of young science-fiction fans, based in New York City, called the Futurians, which included Isaac Asimov and Mary Byers, who would later become Cyril’s wife. (A charming possible fact: it is suspected that the “M.” in “Cyril M. Kornbluth” — Cyril, in fact, had no middle name — was in honor of Mary.)

Perhaps Cyril’s two most famous stories are “The Marching Morons” and “The Little Black Bag.” Which brings me to the second half of the movie that Jonathan Lethem proposed. In addition to the doc about Cyril’s life, there would be a dramatization of one of his stories. Both “Morons” and “Black Bag” involve time travel; in fact, the former is kind of a sequel to the latter.

In “The Little Black Bag,” a broken-down old physician, Dr. Full, living his life in an alcoholic haze after his medical career ended in disgrace, happens upon a physician’s black bag that seems to have materialized out of nowhere. What he doesn’t know is that this bag has actually come from a future in which (not to put too fine a point on it) stupid people have taken over the planet, enslaving a smaller number of brilliant folks. (The elitism embedded in this concept makes me a bit uncomfortable, but Cyril’s nuanced grasp of irony helps to soften it.) So that their proudly ignorant masters can play doctor, some of the smartypants have invented a medical kit that’s basically idiot-proof: you just set the dial to, say, “9,” touch the device to a tumor and — voilà! — it melts away. (Kind of a Star Trek-y thing.) When the bag accidentally gets left in a time machine, it is whisked back to Dr. Full’s time. Once the old doctor realizes the power of these strange devices, he becomes a huge sensation — until a series of twists, involving the evils of capitalism and a slow-to-react future bureaucracy, leads to his (re-)undoing.

“The Marching Morons” expands on that future world of an ignorant majority and their enslaved brainiacs. Real-estate agent and con artist “Honest” John Barlow suffers a mishap while under anesthesia at the dentist’s (a nod, perhaps, to Cyril’s aversion to dental care?) and goes into a state of suspended animation for several centuries — during which, at one point, his comatose body is used as a mascot by the University of Chicago’s football team. (Cyril had a wicked sense of humor.) Barlow is finally discovered, and awoken, in a distant future in which the masses are under the sway of wildly dishonest politicians, debased and debauched popular entertainments, and totally fabricated news. (Um … yeah.)

Jonathan’s original idea, as I recall it, was for us to make a dramatization of “The Marching Morons” — brought forward to the present day — one-half of our documentary-fictional hybrid movie, with an exploration of Cyril’s life the other half.

And just then, Mike Judge’s film Idiocracy came out — based on kind of the same premise as Morons — and Jonathan and I both sighed and went, Well, there goes our project.

That was back in 2006. Since then, Jonathan had moved to Southern California to be a professor while also exploding in popularity as a writer (totally deserved — he’s awesome) and we fell out of touch.

Until a few months ago when, facing into forbidding emotional headwinds and an uncertain professional future, I flashed on our old idea and decided to try getting back in touch with him. The old email address I had for him didn’t work anymore, so I made one up, including his name and the college he’d been teaching at, and shot him a message. I was happy when it didn’t just bounce back. And even happier when he responded, saying that he still thought about our old film project — and regretted that we’d never gotten to do it!

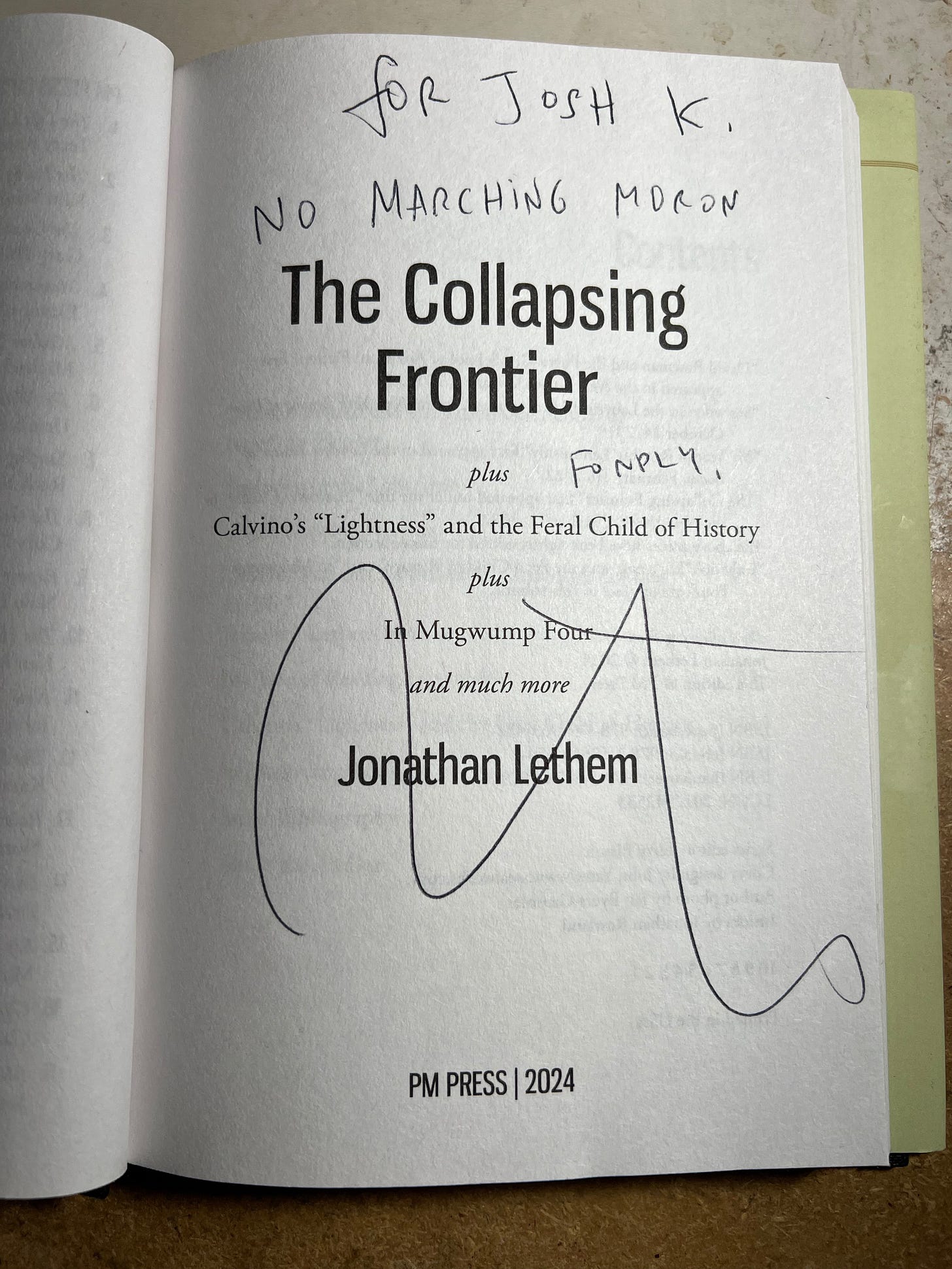

Jonathan mentioned that he’d be giving a reading (and doing an interview) at the wonderful Pegasus Books in downtown Berkeley, where he had once worked (he’d also worked at the indispensable Moe’s Books). This was just before my depression shut me down to the point that I could no longer bring myself to leave our home — it may even have been the last time I went out for months. As I do when I’m out and about while fighting the deep-sads, I felt a kind of impostor syndrome, as if I were engaged in a poor attempt to play my ordinary, non-depressed self. But when I walked into the store and found myself surrounded by the beautiful, infinitely complex souls of books and booksellers, I cheered up. And when I joined the excited group of attendees who were already filling most of the folding chairs — including several writing luminaries — I felt even better. Finally I spotted Jonathan, whom I hadn’t seen in years — and he called me over and spoke to me warmly. (I hadn’t been absolutely sure he’d remember me after all those years!) After he autographed my copy of his new book — The Collapsing Frontier, a delightful, slender collection of fiction and nonfiction, along with a great interview of him by the late Terry Bisson — I took a seat and thoroughly enjoyed the whole event. Along with grooving to Jonathan’s words, I was remembering how bookshops have always sustained me.

When I was a kid, my dad used to take me to the (now closed) New Yorker Bookshop on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Dad claimed to have the longest-standing charge account at that magnificent store. We’d enter on the ground floor, where they sold their periodicals, and then climb the narrow, groaning stairs to the capacious second floor. I’d first run over to the children’s section, to see if there was a new edition of Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators or of C.S. Lewis’s Narnia series (which for some reason I thought the author was in the middle of writing, even though he’d completed the series three years before I was born). Meanwhile, Dad would get lost — entering a hypnotic, book-induced state that would take him all over the store, from Philosophy to Fiction to Theology to Marxism. You couldn’t get him even to consider leaving the bookshop for at least two hours — so I’d happily sit in a corner and read. My father was deeply in debt, but he made of point of always staying current on his New Yorker Bookshop account. He wanted me to be able, whenever I wanted a book, to just drop in and get it. And I did, a lot. And I’d watch with pride as the bookseller would get out the big, much-used notebook where they kept all the accounts and enter my latest purchase. In an unstable world, being able to get any book I wanted was one of the few things I could count on.

My father’s death — when he was 59 and I was 24 — contributed to my first major depression. And as with my most recent bout, family and friends eventually helped pull me out of it. But also, I started telling stories. Stories initially — almost exclusively — about my dad. So that the sharp edges of trauma could be rounded into a more survivable, more graspable, shape.

I’d been hoping to chat a bit with Jonathan after his reading about reviving our C.M. Kornbluth project — but it turned out that he and his family had to hit the road right away that evening to get back down to SoCal. He asked me to send him an email, to remind him about all this. I did, using the pun-alicious subject line “So Great ‘C.M.’ Ya in Berkeley!” — and I was thrilled to hear back from him soon after, writing: “[I]t seems like an absolutely impossible project … which is probably why I should embrace it. So, let’s say yes.”

I can hardly express to you how happy this made me! Especially given that by this point — it was April — my depression had all but totally incapacitated me. In fact, I immediately became deeply worried that my mood problems would keep me from following up on this amazing chance to collaborate with one of my favorite writers. Indeed, it took me quite a while to work up the energy and focus to get back to my computer and reply to him. But I eventually did, and we agreed to meet up again in June, when Jonathan would be back in Berkeley for a bit. I remember walking to his hotel for our planned early dinner together. It had taken a lot of talking to myself, a lot of working through my extreme frozenness, to get myself to take a shower, get dressed, and then — for the first time in ages — leave our home. The sunlight was very bright, and I felt shaky. I waited a while in the hotel lobby — and then Jonathan came out of the elevator, and he was the same great, gracious, funny guy I used to love hanging out with. We went to a brewpub and I had my first cheeseburger since the extreme diet I’d gone on for six months — and boy howdy, let me tell you: cheeseburgers are awesome! (I also, um, had fries — but don’t worry, the next day I was back on the diet, which I’ll probably be on, albeit at a less-stringent calorie limit, for the rest of my life.)

But of course the most wonderful thing (even better than the burger!) was to be able to chat with Jonathan about his ideas for our movie. We agreed that enough time had elapsed since Idiocracy came out — and besides, we were still so super-into this thing. He told me he was planning to write the narration for the film (a relief to me, as it would spare me countless hours of writer’s block), and he related his idea that I would play Cyril M. Kornbluth himself. His concept was so elegant! It was to “reveal,” in our story, that in fact Cyril had not died in 1958. Instead, like his character “Honest” John Barlow, he’d gone into suspended animation. And now he’d just woken up in our present — and he, this former Futurian who’d been catapulted into the future, wanted to figure out what the hell was going on. So Cyril/Josh would interview actual public intellectuals, from across the ideological spectrum.

Isn’t that cool???

Anyhow, I couldn’t be more jazzed. And it looks like we may shoot our first interview as soon as next month. There are still many things to be worked out. (Funding? Crew? Equipment? Locations?) But hey, give me a no- to low-budget project with a great collaborator and I’m in my wheelhouse. (Which probably explains why my wheelhouse is so ramshackle.)

I’m about to immerse myself in the many writings of my cousin Cyril, as well as the few written accounts of his life. Jonathan assures me that I don’t need to let my teeth actually turn green — poetic license, don’t you know? And I already love drinking black coffee!

As Cyril was a near-exact contemporary of my father’s (Paul was born a year later, in 1924), and they both grew up in New York City, this also will be part of my lifelong effort to reconnect with my father — to try to understand what he went through, including his early years during and after the Great Depression, when Dad found Communism and Cyril found science fiction (though the Futurians’ first meeting was at the Communist Party’s headquarters, so there’s some overlap).

And here’s a kind of link between me and Cyril that I find entrancing: Just as his time-traveling character “Honest” John Barlow emerged, blinking, from a state of suspended animation (and as I will portray Cyril himself doing in our movie), I now find myself finally unfrozen from my own sort of suspended animation, via my depression, and now gaze about in gratified wonder at all the lovely people, and projects, that have — sometimes improbably — waited to welcome me back to the wider world.

Here's a fun tangent. I used to be a big fan of the great science fiction writer and ranconteur Harlan Ellison, who once mentioned Cyril in a memorable anecdote about the far-less-great SF writer L. Ron Hubbard:

I was there the night L. Ron Hubbard invented [Scientology]... We were sitting around one night... who else was there? Alfred Bester, and Cyril Kornbluth, and Lester del Rey, and Ron Hubbard, who was making a penny a word, and had been for years. And he said "This bullshit's got to stop!" He says, "I gotta get money." He says, "I want to get rich". And somebody said, "why don't you invent a new religion? They're always big." We were clowning! You know, "Become Elmer Gantry! You'll make a fortune!" He says, "I'm going to do it."

You had me at Pohl…