I stood waiting at the front door to the Guest House of the Zen Hospice Project, staring at a little label that had been placed under the buzzer: it said, “PATIENCE.”

The fact that the word was in ALL CAPS was, I thought, a bit much. Like, okay, I get it — you folks are evolved and enlightened, unlike, say, the sweaty guy on your doorstep (the Guest House was near the top of a very steep hill).

PATIENCE.

In truth, it was taking quite a long time for someone to answer the door. But this was understandable. On the phone, earlier, Roy, the volunteers’ supervisor, had explained to me that this was one of those very rare times at the hospice when no one was dying.

“No patients?” I asked.

“Well, we call them ‘residents.’ But no.”

I’d been both looking forward to and dreading this day, when I’d take my first volunteer shift. So this news made me feel both disappointed and relieved. Mostly relieved.

Roy explained that due to the lack of residents, they were running with minimal staff.

“A skeleton crew,” I said, cheekily.

“I told your shift-mate, Lisa, not to come in,” Roy went on. “But there is someone in Bed 1.”

“I thought you said—”

“Mrs. Chow [not her real name] is already dead. We’re just waiting for the family to arrive so we can do the death ceremonies. Would you mind coming in for that?”

A BART ride and a long, uphill walk later, here I was.

PATIENCE.

Finally, the door opened and a kitchen volunteer let me in.

A short time later, I started up the carpeted stairs to the second floor, where all the residents’ rooms were and where this dead woman now lay. Climbing those stairs was emotionally difficult for me — dragging myself towards what I instinctively shied away from: coming face-to-face with death. My discomfort was somewhat ironic, as I’d spent decades grappling onstage with the aftermath of my father’s death, following his devastating stroke, at the age of 55 — my age now, as I headed up those stairs.

The scene in Mrs. Chow’s room was serene, even beautiful. A tiny, elderly woman, she had died not long after arriving at the hospice. The nurses had washed her body, and had clothed her in a simple black dress. She lay atop the bed, her arms lightly crossed, her eyes closed, her mouth slightly agape. Numerous lit candles had been placed around the room.

As I looked at her, I felt a surprising calm. At the same time, I couldn’t help but think back to my father’s funeral. I had just flown in from the East Coast to this small town in the Midwest, where my stepmother had heroically been caring for him and their three young children. I hadn’t been there for his death — had not, in truth, been there much for him in the four years since his stroke. And now, in a small room at the funeral home, here he was — or rather, here was his body: embalmed! The embalmers had dressed him in a suit — not his usual attire, when healthy (think denim overalls). And they had (with, I’m sure, considerable skill) endeavored to make him look lifelike. But the effect, to me, was the opposite: he didn’t just look dead — he looked like a thing that had never had a life.

And the funeral service! Here it felt as if we — the family members — were extras in someone else’s script. As the rabbi, who’d never met my dad, said some generic nice things about him that were completely nonfactual, and my siblings and I stifled giggles, I remember worrying that this was not the proper way for grievers to display themselves. But the whole ceremony wasn’t for us, really — and it certainly wasn’t for Dad. It was pro forma. It was The Solemn Thing a Community Did before moving on.

Looking back at us — the surviving Kornbluths — what happened that day was that almost all the grief got pushed deep inside each of us, compacted into something hard. The joy, too — there was no celebration of the actual man we’d lost, the vital, powerful father who (pre-stroke) had always insisted on testing our apartment’s rope-ladder with his full, 230-plus pound bulk before allowing any of his children to swing on it, the husband who constantly — and vocally — delighted in the way his wife's hips swung when she walked. Participating in this rote funeral ceremony, dispiritedly playing the roles of grief-stricken family members mourning a plasticized prop, we became emotionally estranged from ourselves.

Mrs. Chow’s children arrived — two sons and a daughter, all middle-aged like me. And a short time later, an RN named Jeff (I mentioned him in a recent post) entered the room: a soothing presence.

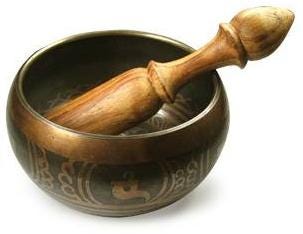

Two ceremonies were traditionally performed after a resident died. Their loved ones could choose to do both, either, or none. In this case, the children had chosen to do both — beginning with the Bathing Ritual. Jeff made a gong-like sound by hitting a bowl three times with a kind of mallet. Explaining everything as he was doing it, he simultaneously emptied two carafes — one containing water, the other a mixture of spices that, he said, had long been used at death ceremonies by Native Americans from this area — into another bowl. He told the family members that that anyone was free to do what he was about to demonstrate: dip a washcloth in the bowl and ceremonially wash Mrs. Chow’s feet, hands, or face.

The family members at first seemed reluctant to participate in this way — and that was fine! Eventually, one of the sons stepped up, dipped a washcloth in the liquid, and washed his mother’s feet. The daughter followed, tenderly washing the face. The second son chose not to do this — and that, too, was fine. Then Jeff turned to me! I was surprised to be included: Wasn’t I just an observer, and a newcomer at that? But the family members looked at me in a way that told me it was okay for me to join in this ritual. So I dipped a washcloth into the warm liquid and ran it over one of Mrs. Chow’s hands.

A short time later, downstairs in the dining room — as an imposingly huge and impressively courteous guy from the mortuary went about moving the body from upstairs — one of Mrs. Chow’s sons approached me. “Excuse me,” he said, “but I wonder if you could tell me the significance of dinging that bowl three times. I mean, why three times?”

“I’m so sorry!” I said. “Actually, it’s just my first day here, and, well, I don’t know anything!” I felt terrible! Was I ruining this experience for him?

But he smiled. “I just ask because I think I’ve seen them do it on Star Trek.”

And now I smiled. “Well,” I said, “then we know it’s got gravitas.”

The huge man from the mortuary was now wheeling a gurney carrying Mrs. Chow’s body, wrapped in a body bag, out into the backyard, where there was a beautiful garden. It was time for the Flower Petal Ceremony.

The mortuary guy partially unzipped the body bag, then Jeff handed out small bowls of rose petals that had been gathered from the garden. First Jeff scattered his bowl’s contents over Mrs. Chow’s body. Then Mrs. Chow’s children did the same. After scattering my bowl’s petals, I looked over at the mortuary guy, who was standing a few steps away, his arms folded respectfully in front of him. There was an extra bowl of petals, and I brought it over to him, so he could join us in this ceremony.

Us!

When death is detached from life, we become detached from each other, from ourselves. When death is accepted as a part of life — as a feature, rather than a bug — then we may find ourselves together, at home in the world.

After my shift, as I headed back down to the BART station, I could sense that something inside me was beginning to heal.

Josh, you've done it again: brought me to tears when I read your post. Thank you.

Tender beautiful writing. I especially appreciated that death is a part of life, and even before one's termination here, it is possible to understand that there are worse things than death. In this sense, letting go can be a blessing.