The God of Procrastination

Two revelations.

“Daddy, does Luke really believe in God?”

“I’m afraid so, Joshy. For a long time I resisted the idea that Luke’s belief was genuine. But I had a long talk with him last night, and he finally convinced me: he really does believe in God!”

“But— But he’s so smart!”

“I know, my son — I know!”

This issue perplexed me to no end. My dad’s best friend — a man I’m calling Luke — was a huge presence in my life, almost like a second father to me. He was dazzlingly smart — spoke several languages and had a master’s degree — and, like Dad, he was a passionate Marxist. They agreed on so much — so why this one, huge difference of opinion?

The God thing, I knew, was a big effing deal. Did an all-powerful, omniscient being form our universe or not? Did someone Up There love us, despite any terrible things we might have done, or thought?

My father, Paul, had always been quite clear on the subject: Of course there was no God! That was superstition, a myth. “The onus,” he’d say, “is on the believers to provide evidence of God’s existence. And they haven’t!”

And yet Luke really, really did believe. Dad was now convinced of that. Huh. Wow! I had to sit with this for a while, let it sink in. Having given up the ghost (so to speak) that Luke was secretly harboring apostasy, I still loved and respected him, no less than I had before. I didn’t feel more distant from him. In fact, in my six-year-old heart of hearts, though I remained staunch in my atheism, I somehow felt closer to him — as if this obvious flaw in his worldview made him less perfect and thus more like me, a kid with a mass of fears and insecurities and worries. More than that, perhaps: If Luke felt so vulnerable that he needed God as a crutch, maybe he needed me too.

Before going any further, I feel I should mention that Luke was a Presbyterian minister.

When I was a small child, Luke lived down the hall from us at 272 East 7th Street, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. On Sunday afternoons, after preaching at his church in Greenwich Village, he’d show up at our apartment, still in his preacher’s garb. After quickly unclipping his clerical collar — which I always found super-cool, like Superman casually revealing himself to be Clark Kent — he’d sit down with Dad at the kitchen table (“kitchen” being a euphemism — there was one basic room, as my father had knocked down almost all the walls, much to the landlord’s dismay) so they could share some cheap wine and talk for hours: about Marx, and revolution, and the civil rights movement. And God.

For an atheist, my father talked — and thought — about God a lot. And he read the Bible constantly. He collected many versions, though the King James translation was his favorite by a mile. Two of his heroes were Harvard theologian Harvey Cox and Catholic activist Dorothy Day, both major figures in Liberation Theology. So he and Luke had plenty to talk about, in enormous detail — and as I listened to them, sometimes while soaking in the “kitchen” bathtub nearby, I tried to absorb what I could. But it was fine with me that I didn’t understand much of what they were saying. In fact, I think I found it comforting, somehow: knowing that these two men, both so dear to me, were bonding in their private language.

Dad loved going to church. He’d say, “It’s the best show in town for a buck!”

One Sunday (he had me on weekends) he took me to a Catholic service in Greenwich Village. It’s possible that we were the only Jewish atheists in the congregation. During Communion, I followed everyone else up front — and when the priest placed the wafer on my tongue, I politely said, “Thank you.”

Apparently you weren’t supposed to say “Thank you.” The priest made a fuss, and Dad was outraged. The Kornbluths would never darken this church’s door again!

After we’d stormed out, we passed another church — this one being of the Presbyterian denomination. We slipped inside.

A tall, handsome preacher was speaking of the long struggle against racism, buttressing his remarks (as preachers are wont do) with copious quotes from scripture.

This was more like it!

Afterwards, Dad went up to the minister and they had a warm, animated conversation.

I have a deep memory of this being how we met Luke — though I also can’t remember a time before he was our neighbor. So did Luke move into our building sometime after we met him at his workplace? Or was he already our neighbor when we stumbled into his church?

Honestly, I don’t know! Sometimes the truth can be hazy.

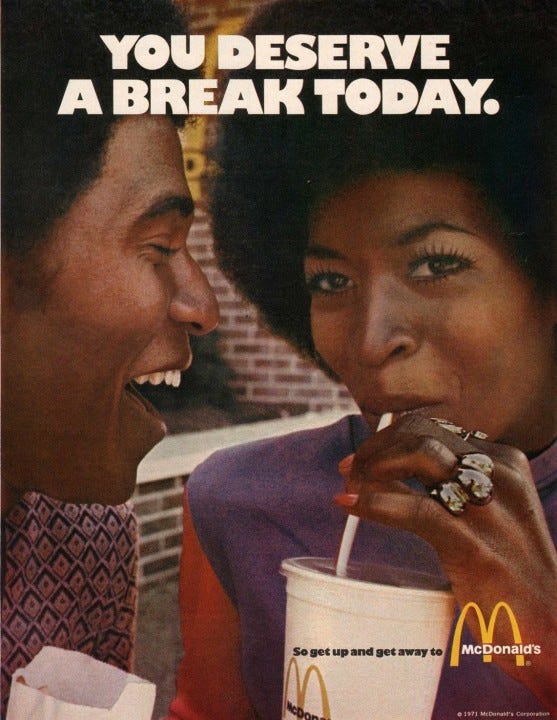

At one point Luke left that church and became a pastor in New York City’s prison system. He was a fierce advocate for inmates’ rights, but his advocacy — and his playful sense of humor — got him into trouble when he gave a bunch of prisoners straws from McDonald’s imprinted with their advertising slogan “You Deserve a Break Today.”

The authorities were unamused. Luke got fired, and began working a series of freelance preacher gigs all over the city. Because he spoke fluent French, he frequently filled in at a Haitian church in Queens.

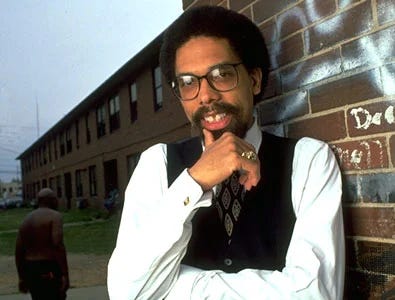

At the same time, he decided to go back to school and work on getting his doctorate at Union Theological Seminary, where he was assigned, as his dissertation advisor, a brilliant young scholar named Cornel West.

By this time, Dad and his girlfriend, Sue, had moved uptown, to 173rd Street in Washington Heights — so I could go back and forth more easily to my mom’s place, on 162nd Street. When he and Sue decided to get married, Luke was the obvious choice to preside at the ceremony. Dad and Luke spent hours in detailed negotiations over the language that would be used. For my father, one thing was non-negotiable: there could be no mention of God.

On the day of their wedding, held in our cramped apartment, my father was worried about Luke getting there in time. Luke got around the city by bike, and he was apparently coming from pretty far away. Finally the doorbell rang. Dad opened the door — and there was Luke, standing in the hallway, clad in a turtleneck shirt and a bead necklace. (Hey, it was the Sixties!)

My father was aghast. “Luke,” he demanded, “where is your clerical outfit??!”

Apparently, for my dad, though God was verboten at his wedding, it was nonetheless de rigueur that the minister be dressed as, you know, a real minister.

Smiling, Luke rolled his bike forward so it could be seen in the doorway. Draped over the handlebars, all nice and pressed in a dry cleaner’s bag, was his official religious garb.

I’d rarely seen my father so relieved.

Luke started filling in at a Presbyterian church in Washington Heights, near us. As he still lived down on the Lower East Side, he got into the habit of biking all the way up Manhattan to our place on Saturday evening, then staying overnight before going to preach on Sunday morning.

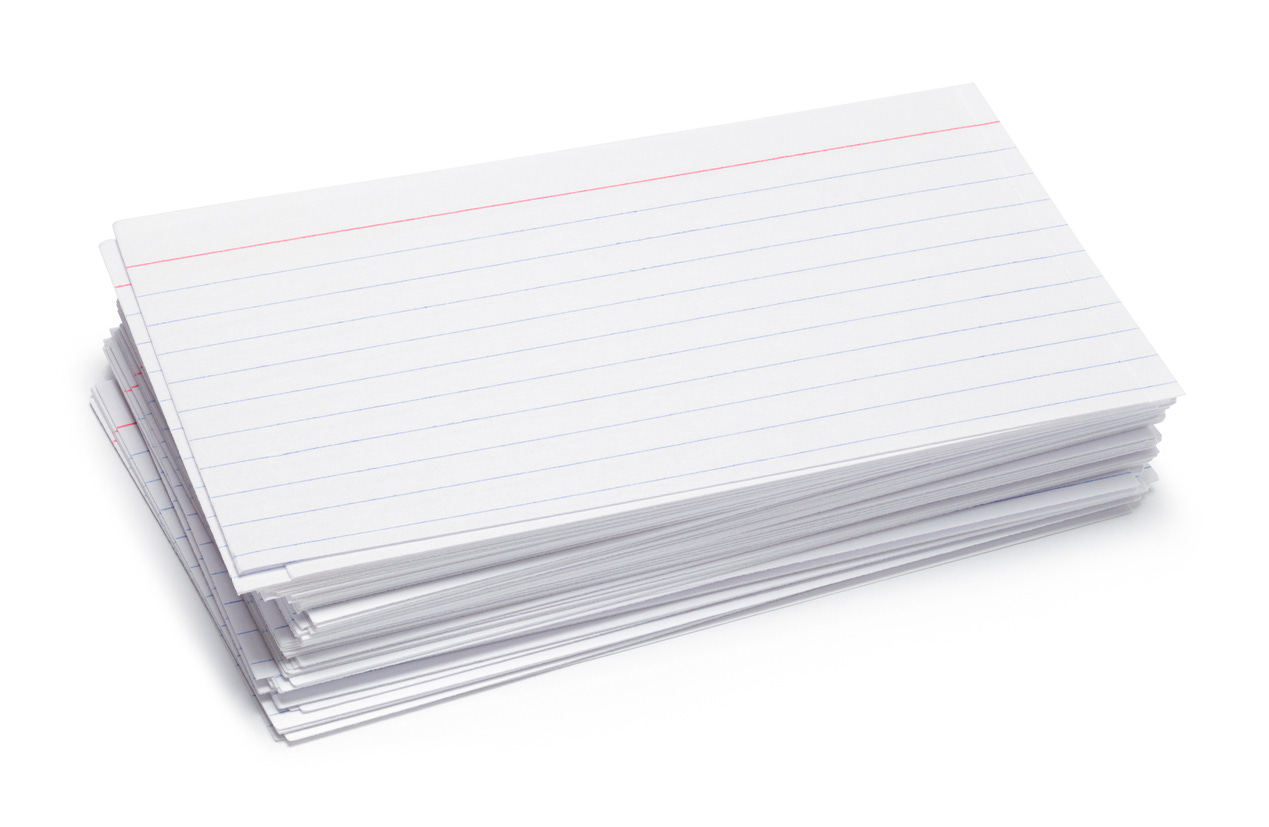

He got into a routine. After having dinner with Dad and Sue and me, and spending some quality time discussing revolution and scripture with my father, he’d prepare to work on the next morning’s sermon. This involved pulling out a pile of blank index cards on which he was planning to write key thoughts and phrases. He’d settle himself into Dad’s prized recliner chair, the Bible on his lap and the cards next to him on an end table, along with a glass of red wine. We all stayed as quiet as we could: the great man was at work!

Often Dad would repair to his and Sue’s bedroom and station himself at his desk, where his growing collection of Bible translations and theology books stared at him from a shelf, and work on his manuscript, Jesus: A Marxist Meditation (which has never been published, alas!). I could hear the clattering of his Underwood manual typewriter coming from behind his closed doors, while at the same time Luke silently pondered his still-blank index cards. Each week it was a struggle for him to get going on his sermon. Another glass of wine, more reading, more pondering. I could feel the tension in him rising. I wanted to help — but how?

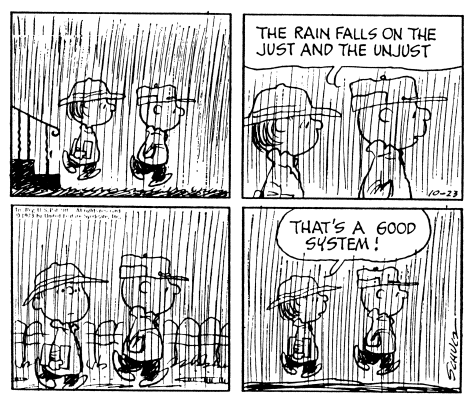

At some point I’d go to my bedroom and set up the guest cot. And eventually, having failed to make headway on his sermon in the living room, Luke — after changing into his pajamas — would bring all his still-blank index cards to my room. He’d put them in a neat pile on one side of the cot. On the other side he made two piles of books: his theological texts, and also my various collections of Peanuts cartoons, which he adored.

As I slipped under my own covers, with the lights still on, I knew — happily — that the evening was far from over. Because Luke had only just begun to procrastinate! That unprepared sermon hung in the air like a spiritual sword of Damocles. The atmosphere was charged with unfulfilled duty. My Saturday nights with Luke were my initiation into the delicious thrill of procrastination — of not-doing — of rebelling against the world’s expectations of you, against your own expectations of yourself. And in this rebellion, Luke’s most powerful weapon was his still-uncompleted dissertation.

“Joshy, may I read to you the latest revision of my introduction? Cornel gave me some excellent notes on the last draft, but I don’t know if I’ve totally clarified my analysis.”

“Of course, Luke!”

And he’d start reading aloud from his dissertation. It was incredibly difficult to follow — with references not only to Biblical passages but also to arguments and counter-arguments and counter-counter-arguments among various radical theologians. The ostensible subject was Martin Buber’s philosophy of “I and Thou.” Buber’s own writings, based on the excerpts Luke read to me, could seem impenetrable, but the basic idea of “I and Thou” appeared to be this: Buber believed that there were two basic types of dialogue. In one — which he called “I and It,” and which was, he said, by far the more prevalent — I think of you as an object, someone (or even something) to persuade, or convert, or even to destroy. But in the other — “I and Thou,” which, Buber believed, occurred very infrequently — I see you, instead, as another subject, a partner in dialogue. I’m not here to convince or change you, or to have you convince or change me; we are here to listen to each other, to be together in mutual care and respect. Buber believed that each time you and I engage in an “I-Thou” relationship — in those rare moments — we are, both of us, simultaneously in dialogue with God.

Which seemed beautiful to me — though what to do with the whole “God” element? Recently, my father had given me a possible way to deal with it, when he mentioned — as we waited for the subway one day — that “if God existed, my son, you could say that He was what all the human beings of the world could do, if only we’d all work together.”

So I could kind of wrap my mind around “I-Thou” — but the rest of Luke’s dissertation, as he’d read it aloud to me into the wee hours, seemed pretty much like gobbledegook: I could make little sense of it. Now, you could say that this was because I was just a nine-year-old atheist trying to understand someone’s doctoral thesis in theology. But as the months went by, and Luke kept referring to his advisor Cornel’s continuing dissatisfaction, I started to suspect that something else was at play. It felt to me — though this seemed quite weird — that Luke was trying to make the language difficult: so difficult, in fact, that any weaknesses in his thinking would be undetectable amid all the confusion. Was Luke in fact turning his thesis-in-progress into an eternal procrastination, a neverending nonstory — the capstone achievement of a world-class procrastinator?

I puzzled over this as I lay there and Luke’s recitation continued to wash over me, his still-blank index cards piled up by the cot. Eventually, I’d drift off to sleep — usually waking, on Sunday morning, to Luke hurriedly fastening his clerical collar and muttering about running late for church. He’d grab the index cards, on which he’d eventually (when? 4 a.m.? 5 a.m.?) scribbled some notes, and go off to get his bike in the hallway and rush off to work.

I’m so glad I’m not a preacher, I’d think, blearily, as I rolled over and went back for another couple hours of glorious sleep.

Many years later I got confirmation from Cornel West himself that Luke had been a problematic advisee. By this time West had become a celebrated activist and author — though not yet a presidential candidate. He was appearing at Modern Times Bookstore in San Francisco’s Mission District, promoting his book Democracy Matters.

After West’s reading and talk, I got on the long line to chat with him and have him sign my copy of his book. He was his usual charming, charismatic self — cheerfully greeting each person as “Brother” or “Sister.” Finally it was my turn. I introduced myself.

“Hello, Brother Josh!” West said, as he began to write an inscription in the book.

“Dr. West, I believe you and I know someone in common — my late father’s best friend.”

When I said Luke’s name, West suddenly stopped writing, and his brow became furrowed. It was the one time at that whole event when he seemed to briefly lose his composure.

After a pause, he finally said, quietly: “Ah, yes — Brother Luke. A most unusual brother.”

My mother, Bunny, with whom I still stayed on most weekdays, also knew Luke — and she kept asking this same question about him: “He’s so handsome — why doesn’t he ever have a girlfriend?”

One Saturday I posed this question to my father.

“My son,” he said, “you’re old enough to know this: Luke is gay.”

This came as a shock to me. My parents had always told me that homosexuality was an illness — in fact, this was part of the official Communist Party line (yes, the same Communist Party that still thought Joseph Stalin was all that and a bag of chips — I’ll get to that in a bit). It had been made clear to me that to be gay was to have something seriously flawed — off — about you. So it absolutely threw me to hear this term applied to someone whom Dad and I loved and respected so utterly.

But even more jolting was something I saw at the same moment. Just as Dad was telling me that Luke was gay, Luke himself had been ambling into the living room, a smile on his face. When he heard my father’s words, his expression immediately collapsed into one of abject horror. And then I became aware that he was now examining my face — trying to make out what my reaction would be to this news. In that instant I knew something with absolute certainty: I needed to show Luke — in my expression, in my manner — that I still loved him. Loved him, if possible, even more than I had since learning that he really, truly believed in God. Because I now knew something that, I sensed, was at least as intrinsic to who he was — to his beautiful, unflawed soul.

During dinner, and afterwards, I could sense Luke’s discomfort at my father’s revelation. Once, when I was just outside the living room myself, I heard him whisper to Dad, urgently, “Paul, why did you tell him?”

“Luke, he should know!”

That night I took special care making up the guest cot for Luke — putting crisp hospital corners on the sheets, as my father had learned to do in the Army and passed along to me. I piled up all of my Peanuts books nearby on the floor, put on my pajamas, clicked on my little bedside lamp and waited. Eventually, Luke came in, bearing his usual blank index cards, religious texts, and dissertation draft. His chatter seemed, at first, to be more halting than usual. But in time we fell into our usual routine — with him asking me how school was going (I realize that I haven’t told you about how much interest he took in my intellectual and moral development, how much he cared about my own happiness — how much, as I realize even more now, all these years later, he worried about me), then launching into the latest chapter of his thesis (“I’m beginning to suspect that Cornel is getting a bit frustrated with me”), all while those blank index cards waited patiently with their mute white faces.

The next morning, I woke, as usual, to find Luke rushing to get out the door to deliver his Sunday sermon. For the first time ever, on an impulse, I said: “Can I come with you?”

He looked surprised. “Sure!” he said. “But you have to hurry.”

I had never been inside this Presbyterian church, though I’d walked past it many times. As Luke hurried back into the vestry, I took a seat among the gathering congregants. I was shocked at how few people were here for the service — just a scattering in a large sanctuary that had room for hundreds of worshippers. And they were old! (Would I think so now, at 64 myself? No, I’d probably think they were kind of on the young side!)

During the service, after taking us through a few hymns and psalms and frequently complimenting the organist, Luke finally came to his sermon. I could see him leafing through those index cards as he stood there in the pulpit. I don’t remember the exact Biblical passage that he was explicating — but there was a moment when he said: “For example, when my wife and I …”

He suddenly stopped talking. I realized that he was looking straight at me. The silence went on long enough that some of the congregants started muttering. I imagined that he’d frequently used that phrase, “my wife and I,” in past sermons, to be relatable as he made a point.

At last Luke resumed, saying: “I don’t have a wife. But if I did — if I could — I’d want us to be engaged in a true dialogue. …”

Now that Luke could be as open with me about his social life as he was with Dad and Sue, I got to hear about some of the men he went out with. He seemed to be very popular — as befitted an extremely good-looking, intelligent guy with a rollicking sense of humor and an enviable collection of turtlenecks.

Once my mom, whom I’d told that Luke was gay, bemoaned: “He’s so handsome — what a waste!”

I assured her that I didn’t think it was being wasted.

A year or two after my father died, when I was in my 20s, Luke told me about an experience he’d had with my dad back when they were living on East 7th Street.

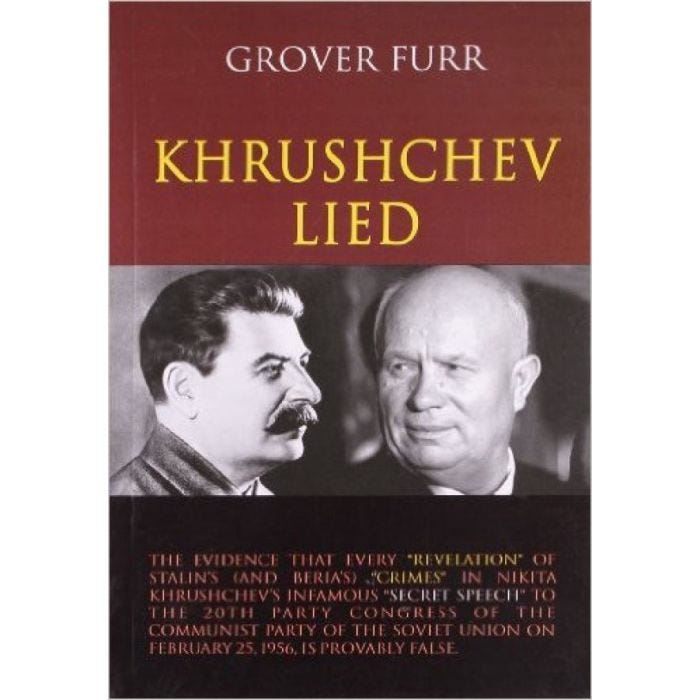

The Communist Party USA had been going through a painful rift. The Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev — in what would later be referred to as the “Khrushchev Revelations” — had publicly denounced his predecessor, Joseph Stalin, as a brutal dictator. My father revered Stalin, and — along with many other Party members, including my mother — refused, for quite some time, to accept that Khrushchev had really said those damning things. Perhaps the English translation had been faulty somehow? But on the day that the translation was finally accepted as legitimate, Luke now told me, Dad went down the hallway to Luke’s apartment and spent the entire day just sobbing.

Over and over, Dad said to Luke, “How could Khrushchev lie like that?”

My father couldn’t allow these new facts to shake his political beliefs, which were so bound up with the myth of a good and noble Stalin at the head of a perfect socialist state. Luke knew the truth of Stalin’s evil monstrousness, but he devoted himself to comforting my dad as best he could.

As I think back to the urgency with which Luke told me about this long-ago incident — I could tell it was something he felt I needed to know about, something crucial — I’m struck by how it resonates with the question I asked my father when I was a child: “Daddy, does Luke really believe in God?” And by how, in answering me, he referred to a conversation he’d had with Luke the night before, the one that had finally convinced him of Luke’s genuine belief.

Was that part of the same day-long conversation in which Dad had asked Luke, over and over, how Khrushchev could have lied? Two dear friends, grappling with each other’s faith?

In the early ’90s I received a postcard from Luke at my little basement apartment in San Francisco. On the front was a beautiful landscape photo of Carmel, Calif. On the back his message began, “I never thought it would end this way.”

Luke was dying of AIDS.

Devastated, I headed out with my girlfriend, Sara, to visit him in Carmel. He was staying with a group of women who had taken him into their communal home decades earlier, when, as a young man grappling with his sexuality, he had fled his intolerant family in Southern California. Back then, these women had given him a nurturing space where he could feel accepted and valued. This was where he wanted to spend his final days.

I think it is the most beautiful place I have ever been.

At the beach, Sara and I stood on either side of his wheelchair as the three of us watched the sunset. Then we went back to his guest cabin.

“Josh, I want you to have my books and papers,” he told me. We helped him pack them into boxes. Bibles, of course — in various languages. Theological tomes: Buber, Cox, Reinhold Niebuhr, and numerous others. His bound dissertation on “I and Thou,” which he had eventually completed — to the immense relief, I imagine, of Dr. Cornel West. And his scribbled notes for various papers and sermons — including many, many index cards.

I have all those boxes in a storage room, and I’m feeling an impulse to go through them. After all this time, I’d like to try reading his dissertation — to see if I can understand it any better now, after all those years. Sitting here at my desk, typing these words, I can remember exactly how his voice sounded on that pivotal Saturday evening, after my father’s revelation, as Luke began to read aloud to me from whatever draft he was on. How he sounded shaky at first, as if he were unsure of how I felt about him now. How it struck me as vitally important that, even in my silence, I beam him a message somehow, from the depths of my soul to his: I love you. We are dear friends, forever. You and I. I and Thou.

I remember you talking about Luke in one of your monologues, specifically describing your father telling you he was gay, his reaction, and your efforts to make sure Luke knew you still loved him. It's good to learn more about him.

The best tale yet. A perfect parallel of the two men dealing with their two respective faiths. You were a good kid!