Francis Ford Coppola wanted to know what I had against playing a cigarette pack. A fair enough question — especially coming from one of our greatest living directors.1

I’d been cast in a small role in a movie called Jack (1996), a vehicle for Robin Williams. Williams was to play a 10-year-old boy who, because he suffered from a rare disease that made him age four times too fast, had the body of a 40-year-old.2

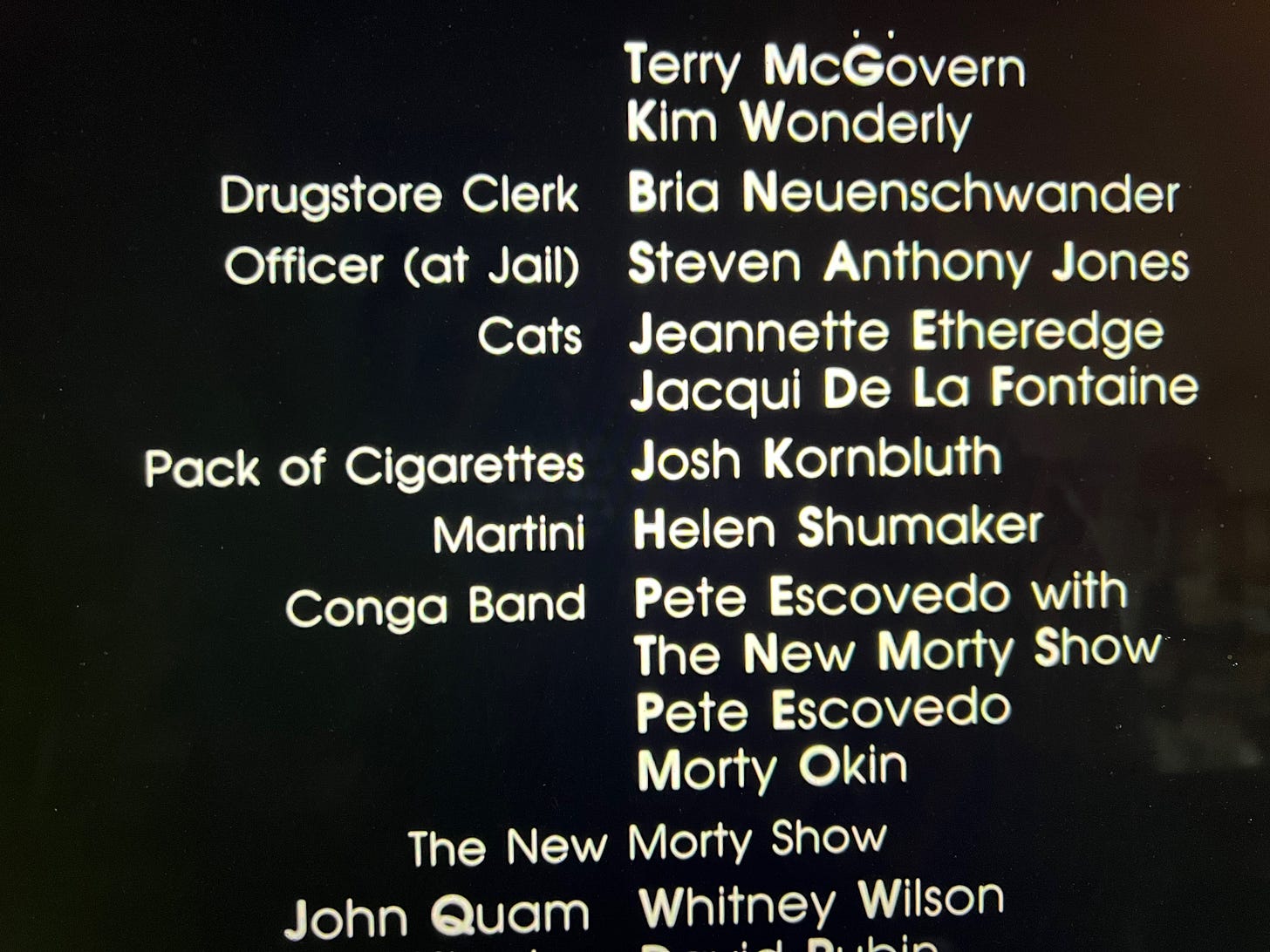

My scenes would all happen during the opening title sequence. Jack’s mom, Karen (Diane Lane), dressed as the Wicked Witch of the East from The Wizard of Oz, is attending a Halloween costume party with her husband, Brian (Brian Kerwin), who is dressed as the Tin Man. Joining them in a long conga line, as a band plays, are two of their friends, one dressed as a giant cigarette pack and the other as a martini. When Karen unexpectedly goes into labor (she’s only 10 weeks pregnant, but it turns out that the gestational process is four times faster as well), Brian calls out for help to their friend the cigarette pack (“Josh!”), who ends up driving the couple and the martini woman to the hospital. (More on this drive later.)

When the local casting director3 told me I’d landed the part of Cigarette Pack and showed me the script, I had some reservations. In a movie that clearly seemed to be aimed at a young audience, was it morally offensive, I wondered, to portray a guy happily dressed as a pack of cigarettes? Wasn’t that sending a message to kids that smoking was fun? The casting director said she’d convey my concerns to Francis (everyone called him Francis; on the set, when I addressed him as Mr. Coppola, he said, “Call me Francis”). The next day, she got back to me: Francis said I could submit an alternative costume idea for him to consider. After much deliberation, I suggested that I instead portray Leon Trotsky with an ice pick through his head.4 The word quickly came back: “Francis said to stick with the cigarette pack.”

But I still had misgivings. I’d recently interviewed Wallace Shawn for a magazine. Though he’s mostly known as a character actor (Vizzini in The Princess Bride, “this little homunculus” in Manhattan), Shawn is a tremendous playwright: not just as co-author of the movie My Dinner with Andre, but also as the writer of challenging, often disturbing plays that frequently deal with the hard ethical choices we all face under late-stage capitalism.

I dug up Shawn’s phone number from that interview and left him a message on his answering machine,5 asking whether, as a performer trying to live a moral life, I should turn down a role as a guy dressed as a cigarette pack.

To my surprise, a couple of days later he left me a message in response: “Josh, it’s Wally. Sorry for the delay — I’ve been traveling. I’m calling you from a phone booth at a gas station. I’ve been thinking about your question. Now, if you accept drama as a legitimate form — and by no means do you have to do this — but if you do, then that means you need to have a protagonist and an antagonist. Francis Ford Coppola is a great filmmaker, and I seriously doubt he would portray a man dressed as a cigarette pack as a good person. So your character is almost certainly an antagonist, and would thus be serving his proper role in a drama. In which case, I would venture to say that your taking this role would not be an immoral act.”

I agreed to play the cigarette pack. Mostly, I needed the money.

The first thing I needed to do was get fitted for my costume in an office in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood. It was there that I first met Helen Shumaker, who had been cast as the martini. For years I’d been in awe of Helen for her stunning, powerhouse one-woman shows. Her performance as the title character of Mona Rogers in Person, written by her great collaborator, the late Philip-Dimitri Galas, revolutionized my ideas of what was possible for one actor to do onstage: she berated, she accused, she belted out torch songs. Helen’s stillness onstage was stiller than anyone else’s stillness — this tiny woman exerted a powerful gravity that just kept you riveted: a living, emoting black hole.

So I was quite nervous to meet her — terrified, even. And what I realized right away is that, when she’s not in character,6 Helen Shumaker is a singularity of sweetness. We immediately started calling each other "Toots" and "Sweetie" — and continue to do so.

On our first shooting day, Helen and I showed up at the set, a legendary North Beach club called Bimbo’s 365, and got into costume. My cigarette pack outfit was, truth be told, pretty cool: it even had cigarette stubs that I could release from my shoulder area by pulling out a wooden button thingie. Helen’s martini costume came complete with a pimento-stuffed olive on a toothpick and contained actual liquid, which sloshed around as she moved. This last feature would become a problem during filming, especially as we danced in the conga line: the martini glass started leaking, causing some other costumed dancers — monsters, dwarfs, an endless number of Marilyn Monroes — to go slipping and sliding. Between takes, crew members would crowd around Helen, futilely trying to plug the leak.

As the crew set up for the very first shot, all the actors got into position along the conga line. I was right in front of the stage, which was occupied by the band.7 After those misgivings I'd had about playing a guy happily dressed as a giant cigarette pack, Wallace Shawn had helped me find an internal peace. So it came as quite a jolt when, just as they were about to start filming, one of the musicians onstage leaned over and said to me, "Josh Kornbluth, I cannot believe that you, of all people, would stoop so low as to take a pro-cigarette gig!" At which point, Coppola yelled, "Action!" In that first take, my initial expression was probably one of shock and embarrassment — not at all appropriate for a guy happily participating in a conga line. But by the next take, I'd pulled myself together: hey, I'm a professional.

My second scene was at the hospital where Diane Lane’s character, still in her witch costume, would be rushed to the delivery room. As we prepared to shoot at an abandoned medical facility, I chatted with Francis in the waiting area, mostly about our fathers, whom we had adored. Francis’s dad, Carmine, a musician and composer, had died a few years earlier — of a stroke, like my dad. We talked about how much we missed them.

This hospital sequence involved a number of vaudevillian sight gags. In the context of the full movie, these happen in a flash — all part of a brief set-up for the main plot. But from my Rosencrantzian (or possibly Guildensternian) perspective, this was a momentous section of the film, in cinema history akin to the bridge being blown up over the River Kwai. So I’ll take you through it step-by-step.

Our party of four — Witch, Tin Man, Cigarette Pack, Martini — needs to get through security, where they have set up one of those little metal-detecting doorways.

First Helen’s martini glass has a hard time squeezing through the detector, as the Tin Man, who has been repeatedly setting off the alarm, frantically empties his pockets. Finally his wife, the Witch, calls out from the gurney that it’s his metallic costume that’s causing the ruckus. (Duh!)

Next it’s my turn. The first problem is that I am smoking a cigarette. (Yes, the guy dressed as a cigarette pack in a children’s movie was also someone who’d smoke a cigarette in a hospital! All I can say is, this wasn’t in the original script.) A disapproving nun8 in the lobby points out that this is against the rules.

My character responds in a classically passive-aggressive manner — by putting out his cigarette in the nun’s coffee. (Maybe that’s just aggressive-aggressive.)

He then briefly gets stuck in the metal detector …

… before figuring out he can get through it if he turns sideways.

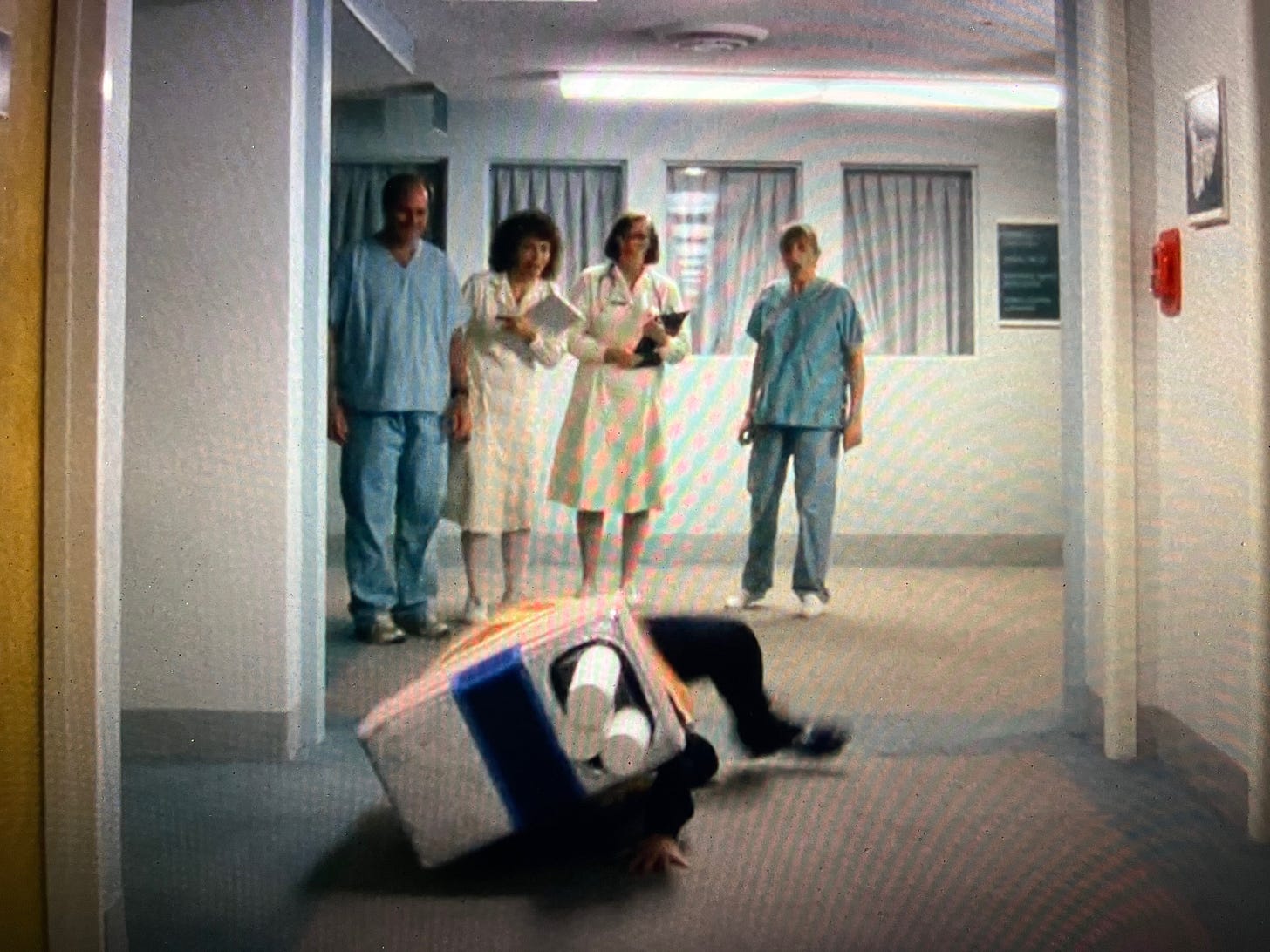

We have now reached a crucial moment in my performance. I was going to have to execute a classic sight gag: a pratfall. In the story, my struggles at the security checkpoint had caused me to lag behind my friends, and I needed to hurry to catch up. I was to round a corner and then, as I scurried down the hallway, I was to trip and go sprawling, all in my cigarette-pack outfit. I mentioned to the other actors that I’d never done anything like this before. So Diane Lane showed me a trick for how, when you’re running, to come to a dead stop while the rest of you goes flying: the key was to jam a toe into the heel of your other shoe — the laws of momentum would cause your upper body to keep going at the same speed even though your feet were now firmly planted.

As I waited to perform this gag, I saw Diane, in her witch’s costume, watching me with great concern from an off-camera alcove. Coppola called “Action!,” I started running, and as I charged around the corner, I saw Diane actually praying for me, with her hands tightly pressed together and her eyes squeezed shut. As she had taught me to do, I jammed a toe into the heel of my other foot. It felt like I was flying through the air for minutes, though it was only a second or so, and then I was landing — splat! — on the floor (fortunately, the cigarette pack cushioned the impact a bit), before quickly getting back up to my feet and continuing to run, stooping to pick up part of the witch’s costume that had fallen to the floor as Diane’s character was being wheeled into Delivery.

When I successfully completed my pratfall in one take, there was a huge round of applause from a relieved cast and crew. I felt a swelling sense of pride, in the knowledge that I’d now, in my own small way, joined cinema’s storied club of physical comedians. I looked forward to relaxing for a while and then seeing everyone else at the next meal break, when perhaps folks would stream by to offer their accolades. Just then, an assistant director came up and told me that I should quickly prepare to replicate that run-and-fall umpteen times, as they were going on to film the main action of the scene — Diane’s character being wheeled into the delivery room — with me taking a tumble (over and over, take after take) in the blurry background.

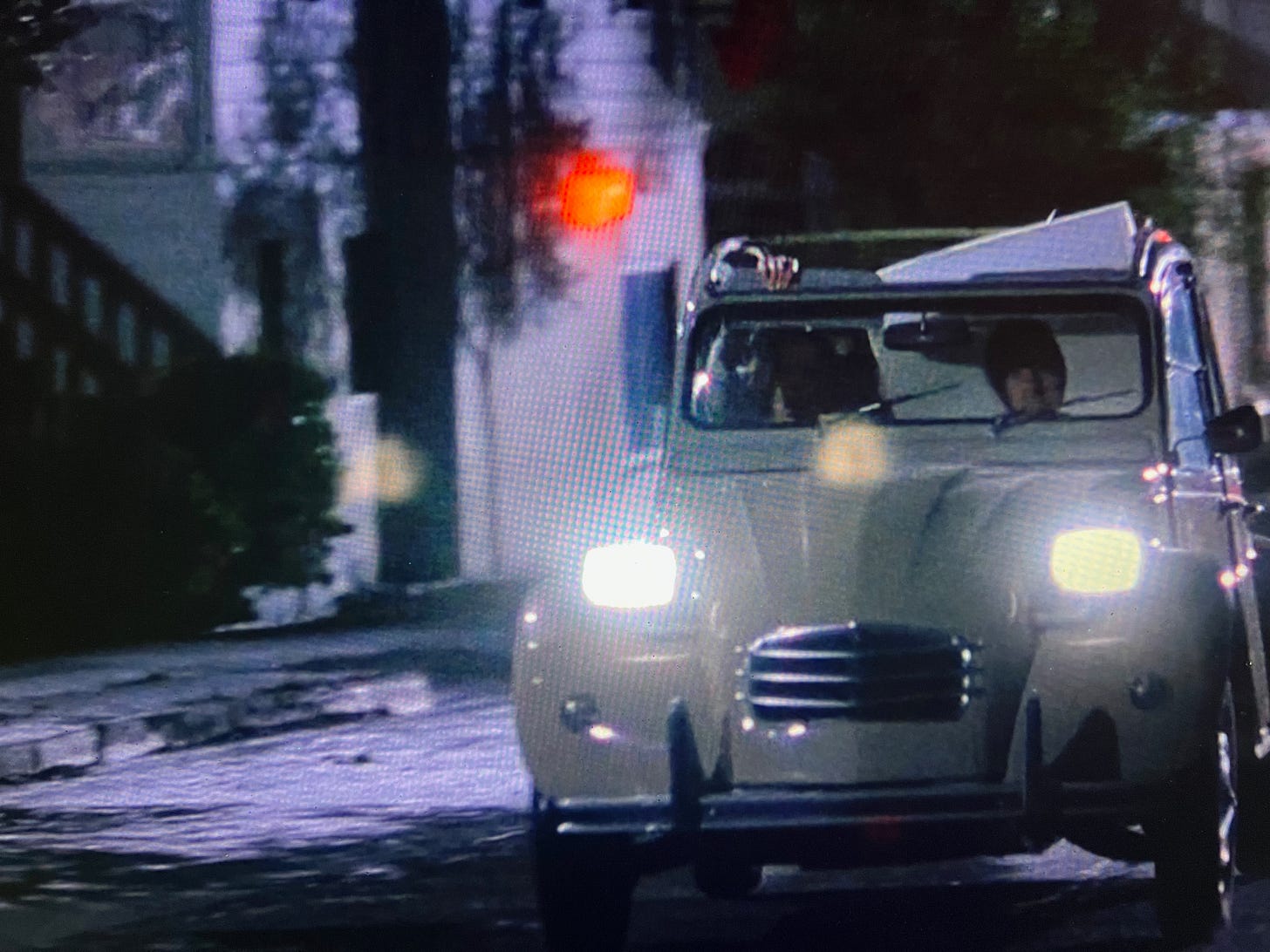

After the hospital shoot, I got a call from the casting director: they were adding another scene, and I was going to be in it. In this new sequence, my character would be driving his three friends — the Witch, in labor; the Tin Man, her husband; and the Martini — to the hospital at night.

The casting director said she had one big question for me: Did I know how to drive a stick shift?

Long pause.

“No,” I answered, truthfully.

I was leaving something out: I didn’t know how to drive at all.

“Well, you’d better learn quickly,” she said. “We shoot in a week.” She went on to tell me that this wasn’t going to be just any car — it was Francis’s own vintage Citroën, which he’d had shipped over from Europe.

Right away I got a DMV driver’s handbook from the library, crammed for my learner’s permit, and passed that test. Then I called a driving school and arranged to start taking lessons immediately. My driving instructor picked me up at my apartment in the Mission District, told me to get behind the wheel, and began to show me how to drive a stick. It didn’t go very smoothly, to put it mildly — there was lots of stalling, and certain things were said by other drivers that could not easily be unsaid — but we eventually made it up and over a few hills. I started to feel more comfortable. As I drove us along the Panhandle, abutting Golden Gate Park, I noticed something.

“Hey,” I said to my instructor, pointing, “isn’t that a famous gas station? I think I just read about it.”

The instructor lunged to grab the steering wheel; apparently, I had been veering into another lane of traffic.

“Pull over,” he said.

When we had come to a stop by the curb, he told me how it was really important, when driving, to keep my eyes on the road ahead of me, and not to go looking off (much less pointing) elsewhere. His own eyes seemed to fill with a strong emotion. “I have a family,” he said. “Small children. This lesson is over.”

He drove us back to my apartment and dropped me off.

A few days later, on the night before the shoot, the casting director called me. There had been a change of plans. The next day’s forecast called for rain, so they were going to do the scene as a “process shot”: The car would be stationary, inside a soundstage. I’d pretend to drive my three friends down a San Francisco street at night, while crew members would move lights over the car’s surface to simulate the illumination from streetlights. Then, using filmmaking magic, the car would be edited into an actual exterior.

Now you may be wondering, dear reader, how, having made such a stink about playing a cigarette pack, I, a non-driver, could possibly have contemplated driving three of my fellow humans, one of them movie-pregnant, in a car, and not just any car but one with a funky European stick shift, at night. I mean, you don’t need to go consult Wally Shawn to figure out the ethics of such behavior. All I can say is, I’m pretty sure I never would have gone through with it. I mean, we autobiographical monologuists may be somewhat solipsistic — even, at times, a tad narcissistic — but we’re not monsters, okay? I guess I had faith that the God of Bit Players would be looking out for me. And it turned out that my faith, in this case, was rewarded.

Postscript: A few years later, I was interviewing Robin Williams for San Francisco magazine. As we were setting up, I mentioned to him that I’d been in one of his movies, Jack, as the Cigarette Pack. “But they didn’t give me any dialogue,” I complained. “You were filtered,” he replied, instantly. R.I.P., sweet genius.

A complete list of actors who have been directed by Coppola would include, among others, Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Diane Keaton, Robert Duvall, Laurence Fishburne, and me. I’ll just leave that there.

I’d love to be cast in another Coppola film at some point, so I’m going to be circumspect about the quality of Jack as a movie. Rotten Tomatoes gives it a 17 percent positive rating. It was nominated for Worst Picture at the 1996 Stinkers Bad Movie Awards, ending up second to Striptease.

Davia Nelson, one of the Kitchen Sisters, hosts of the great, eponymous podcast. The Jack production was packed with amazing Bay Area talent: actors, musicians, podcasters … I mean, just wow!

This was a horrible suggestion — potentially even more traumatic to a youthful viewer than a cigarette pack. My only excuse is that, growing up in a household of Stalinists, I spent my childhood hearing my dad condemn “Trotskyites” as the worst of the worst (it was a sectarian thing). So a portrayal of Trotsky being assassinated in that grisly manner on the orders of his archnemesis Stalin had embedded itself in my subconscious as a happy image. I guess.

A note to my younger readers: this was before voicemail. Oh, and also cellphones.

Brother Jacob and I cast her in both of our feature films together. In Haiku Tunnel (2001), she plays the scary head secretary Marlina d’Amore. In Love & Taxes (2015), she’s the intimidating tax attorney Mo Glass.

The bandleader was played by the great percussionist Pete Escovedo, father of percussionist/vocalist Sheila E.

Between takes, try as I might, I could not get the actress playing the nun to stop glaring at me — she stayed ferociously in character, or maybe she just didn’t like me. This got me kind of rattled, but like any true practitioner of The Method, I ended up using it as part of my character’s motivation.

Thank goodness you got this gig before the advent of The Self-Driving Car. That would have simplified your fate. Also, with gas prices as fluctuated as they currently are fluctuating, the scene could have been cut for lack of budget. In addition, as well, it's hard "being a box", but we know you are friends with many mimes, so you were able to figure that one out. Thanks!

Fabulous read