Lordy, There Are Tapes!

Trying to stay afloat on 54-year-old waveforms.

My professional training — to the extent that I have any — is as a copy editor. Give me a good ballpoint pen (I’m currently partial to the Uniball Vision Elite with blue ink1) and I’ll go to town on your printed-out rough draft. Or sit me down in front of your Word doc on a computer screen and watch my editorial fingers fly across the keys. (But may I take just a moment to pour one out for the old version of WordPerfect that used to run on the DOS computers of my secretarial years? I was the Michael Jordan of that word-processing program — leaping at a moment’s notice into the “hidden” mode, where I could do anything, before jumping back out into the “regular” text that WordPerfect let all the Muggles see. Once, while riding in a van, I saw a road sign informing us that we were entering the city of Orem, Utah — which, I knew from a screen that appeared every time I booted up my computer, was the home of WordPerfect. I’m not ashamed to say that I shed a tear in appreciation.)

Audio, though. Hmm … no. I don’t feel comfortable editing audio. As far as I’m concerned, that’s one of the Dark Arts — along with editing video … and, well, also whatever it is that people do with Photoshop. In short: I do not wish to live inside an Adobe hut.

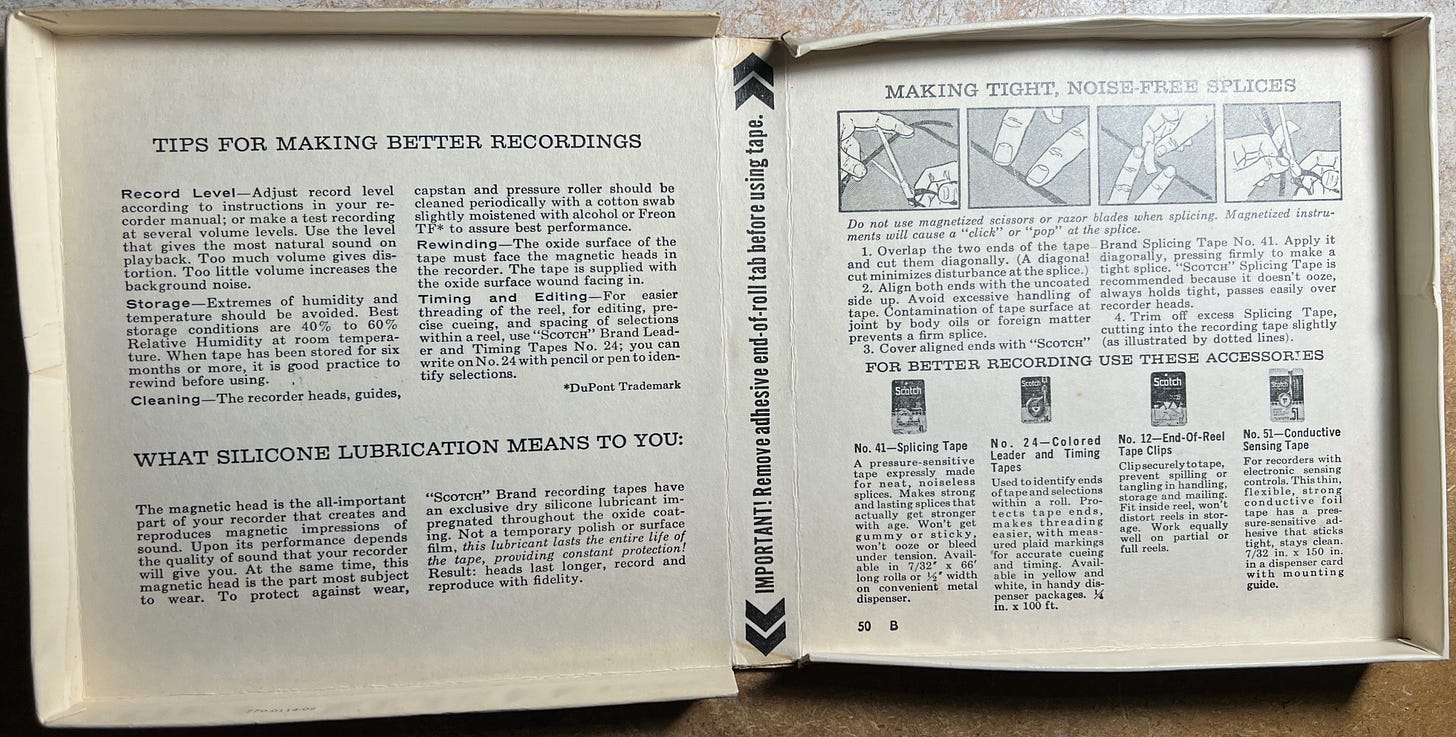

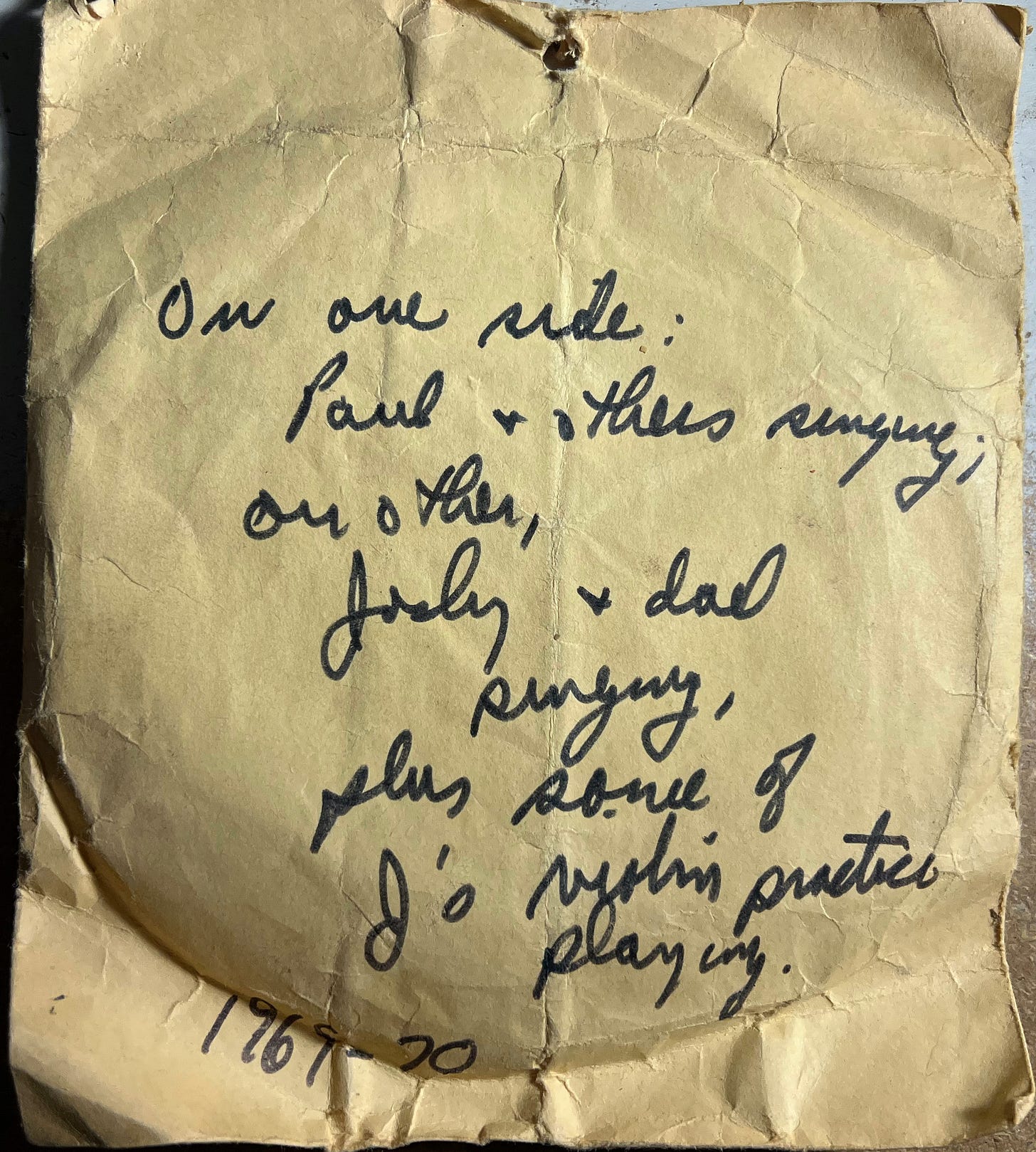

And yet, there are these tapes, from 1969-’70, when I was 10 or so. My father, Paul, had a reel-to-reel tape recorder back then. I remember him letting me thread the end of the skinny, shinier-on-one-side magnetic tape from one reel through the roller-and-magnet thingamajig in the center of the machine and then onto the empty reel on the other side. There was that moment of anticipation as he used two beefy fingers to simultaneously press the “record” and “play” buttons, and then the two reels would begin to turn. The distant future awaited whatever sounds we cared to produce. Such power!

And yet, staring at these tapes over five decades later, having retrieved them from a sturdy wooden chest filled with Kornbluth family memorabilia that I keep under our kitchen table and open only in the event of an uncontrollable attack of nostalgia, I felt helpless. Dad’s old tape recorder had not survived the family’s many uprootings — so how was I going to listen to the tapes? The first thing I did was call the East Bay Media Center here in Berkeley; in past years, they’d restored many a cassette and VHS tape for me. Alas, they said — they no longer had the equipment to digitize reel-to-reel tapes that were this old. They suggested that I try another Berkeley institution, DeNoise Studios: “Albert is amazing!”

An audio place called DeNoise! I mean, just … wow! It sounds kind of like the way you’d say “of noise” in French. And, from what I can tell, that’s exactly what its founder, Albert Benichou, intended. Benichou may just be The Most Interesting Man in the World. Here’s how he describes his background:

I grew up in south of France, spent a few years in Israel and Morocco, and came to Berkeley in 1998, where I started DeNoise Studios. The business began as a sound mastering facility working with local musicians. I am an artist myself, I write and compose songs. I play guitar and perform in the French/Bossanova style. In 2008, I expanded DeNoise to include video and photo production and I was able to transfer my artistic skills in a way that I can today handle a mic or a lens with the same passion. Every day I pack my bike with equipment and meet different people telling different stories, and there is probably no better place than the Bay Area for this.

When I first called DeNoise, a guy named Alex told me that Albert was out of the country (in Morocco, no doubt, performing with a bossanova band by day while carrying out secret-agent assignments at night2), but would return in a week or so. Of the seven reel-to-reel tapes I’d found, I decided to drop off two, at least to start. Digitizing these things isn’t DeCheap, and also I wasn’t sure that any sound had been preserved on them over the years.

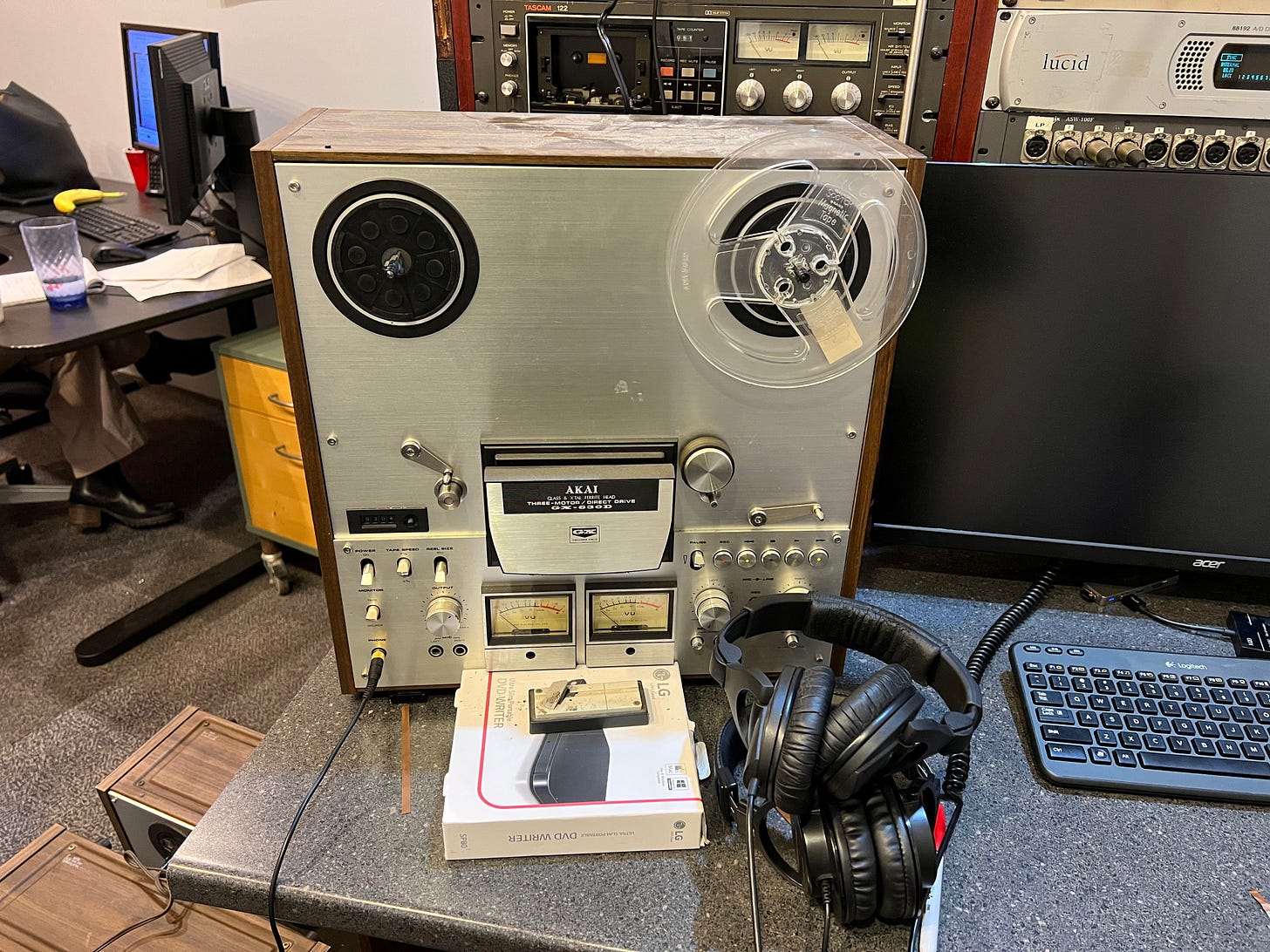

A few weeks later, Albert called to say that he’d finished the transfers. When I biked over to DeNoise Studios to pick up the two tapes, he was at lunch — but Alex told me that Albert had found digitizing them to be quite difficult; they weren’t in great condition. He showed me the first two old reel-to-reel recorders that Albert had enlisted for this task:

Both of these seemed massive, compared to my memories of Dad’s old machine. Sadly, though, neither was up to the challenge. So Albert had no choice but to haul out Big Bertha here:

You can see the unsuccessful machines on the floor below, hanging their tape heads in shame.

Anyhow, thanks to Albert’s (and Big Bertha’s) heroics, I now had four audio files (each tape had two sides) of sounds from way back when. But how could I edit those files down to bite-size mp3s for my family — and for you, dear readers/listeners? Clearly, this was beyond the capacity of my trusty Uniball.

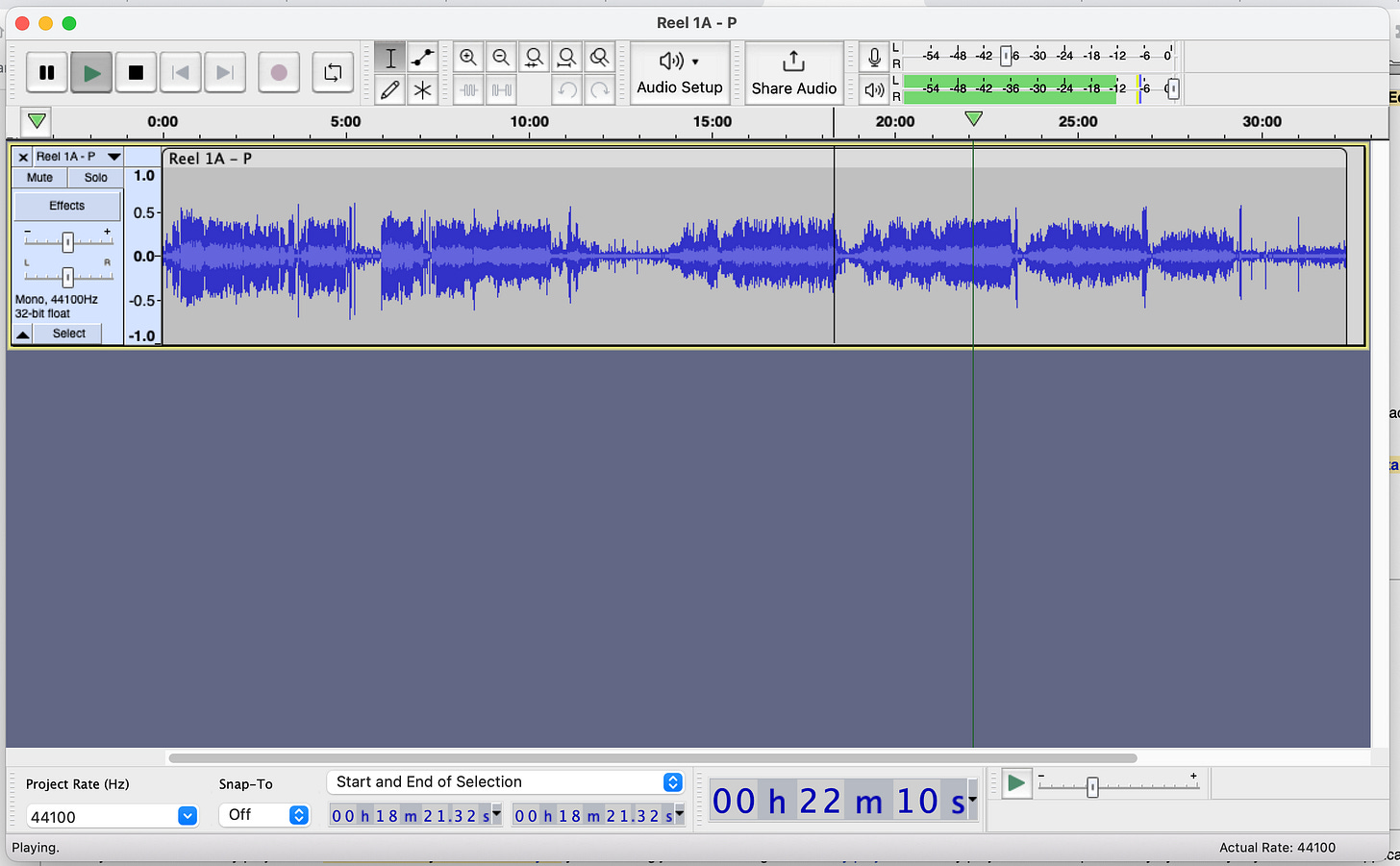

After Googling around for a bit, I downloaded Audacity, which is free, open-source, cross-platform software. Sometimes — okay, many times — I fear for the future of humanity, but then I’m reminded that there are people who create incredible things like this and make them completely accessible to us broke-ass masses. On top of which, they have clearly considered that, among the broke-assed, there may be the occasional 63-year-old who is terrified that he won’t be able to figure out this stuff — so they’ve made easy-to-follow tutorials. Plus it turns out that there are super-helpful how-to videos on YouTube.

The key thing I had to accept was that instead of reading text, I’d be reading waveforms:

Everything that followed, editing-wise, had to do with zooming in and out on these waveforms, selecting chunks of these waveforms, exporting these waveforms — just generally leading a waveform-centered existence. Letting go of text felt kind of sad, like Johannes Gutenberg having to lay off an aging cadre of transcribing monks.

But wow, how magical it was to be able to produce an mp3 file of nine-year-old me singing “(We Are Climbing) Jacob’s Ladder” with my dad (who’s also playing guitar):

Along with the original tapes are large index cards on which Dad wrote the contents. Here, for example, is the card on which he made note of “Jacob’s Ladder” (which was part of a long recording session that was supposedly a broadcast from radio station WSJP, call letters standing for Sue — my stepmother — Joshy, and Paul):

Have I spent an inordinate amount of time lately staring at my dad’s notation “HARMONY! - wow!,” apparently complimenting my singing? Yes, I have.

On the other hand, I think no one needs to dwell on any of the self-recordings of my violin practices that he had me make. This was shortly before my parents — to the relief of our neighbors — came to an agreement that it would be best for me to choose another instrument.3 If you can stand it, here’s me trying to scratch out an arpeggio:

Looking at this passage on Audacity, even the waveform seems to be in pain:

Violin sound-crimes aside, I’m finding the digitized tapes a joy to listen to. I loved singing with my dad. We sang together all the time: at home, walking around Manhattan — we had special songs for going uphill (such as “Song of the Volga Boatmen”), going downhill (“Down in the Valley to Pray”), even strolling through the flatlands (“Come Follow, Follow Me”). One song would flow into another. Here’s an excerpt in which Dad and I sing three songs in a row: “The Water Is Wide” and two rounds, “Dona Nobis Pacem” (Latin for “Give Us Peace,” words that felt particularly meaningful during those Vietnam War years) and “Kum Bachur Atzel” (Hebrew for “Get Up, Lazy Guy”).

I’m looking forward to getting the other five tapes digitized — and I no longer feel quite so intimidated by the prospect of diving into waveforms. If I may paraphrase one of our former presidents: where there is Audacity, there is hope.

Okay, you pen-loving freaks — come at me! What makes and models do you favor? Along with my Uniball fanaticism, I’ll confess to a nostalgia for the Pilot Razor Point felt tip, which my mom used to favor.

This is just speculation on my part.

You know that a boy’s violin playing was terrible when people are relieved to hear him practice the oboe instead.

Oh man, this was great, Josh! That arpeggio was pretty good, BTW! In tune, for starters - which is huge for young violinists. My sense is you gave up way too soon on that. Loved your Dad's heartfelt voice, your wonderful harmony, too. Many thanks, again, for sharing all this and for being such a good human. I look forward to what's next, Sara

I loved that medley, beginning with The River Is Wide and going on to the two rounds. That little-boy you was keeping right up! But also it gave me such a sympathetic view into what felt to be your father's soul...adding to the beautiful complexity of what you portray in your varied monologues. Thanks for this!

Also you've given me courage to try again to retrieve my Mac files from the nineties, long after going over to the, ahem, dark side.